From the earliest days of warfare, it’s never been enough to be able to build a deadlier weapon than your enemy can. Making a sharper spear, an arrow that flies farther and straighter, or a more accurate rifle are all important, but if you can’t make a lot of those spears, arrows, or guns, their quality doesn’t matter. As the saying goes, quantity has a quality of its own.

That was the problem faced by Britain in the run-up to World War II. In the 1930s, Rolls-Royce had developed one of the finest pieces of engineering ever conceived: the Merlin engine. Planners knew they had something special in the supercharged V-12 engine, which would go on to power fighters such as the Supermarine Spitfire, and bombers like the Avro Lancaster and Hawker Hurricane. But, the engine would be needed in such numbers that an entire system would need to be built to produce enough of them to make a difference.

“Contribution to Victory,” a film that appears to date from the early 1950s, documents the expansive efforts of the Rolls-Royce corporation to ramp up Merlin engine production for World War II. Compiled from footage shot during the mid to late 1930s, the film details not just the exquisite mechanical engineering of the Merlin but how a web of enterprises was brought together under one vast, vertically integrated umbrella. Designing the engine and the infrastructure to produce it in massive numbers took place in parallel, which must have represented a huge gamble for Rolls-Royce and the Air Ministry. To manage that risk, Rolls-Royce designers made wooden scale models on the Merlin, to test fitment and look for potential interference problems before any castings were made or metal was cut. They also set up an experimental shop dedicated to looking at the processes of making each part, and how human factors could be streamlined to make it easier to manufacture the engines.

Continue reading “Retrotechtacular: Making Enough Merlins To Win A War”

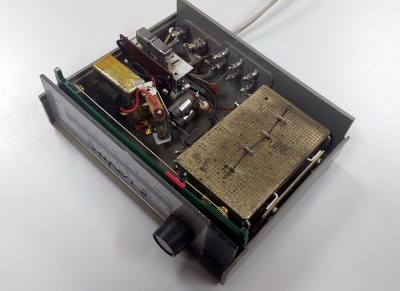

In a Dutch second-had store while on my hacker camp travels this summer, I noticed a small grey box. It was mine for the princely sum of five euros, because while I’d never seen one before I was able to guess exactly what it was. The “Super 2” weighing down my backpack was a UHF converter, a set-top box from before set-top boxes, and dating from the moment around five or six decades ago when that country expanded its TV broadcast network to include the UHF bands. If your TV was VHF it couldn’t receive the new channels, and this box was the answer to connecting your UHF antenna to that old TV.

In a Dutch second-had store while on my hacker camp travels this summer, I noticed a small grey box. It was mine for the princely sum of five euros, because while I’d never seen one before I was able to guess exactly what it was. The “Super 2” weighing down my backpack was a UHF converter, a set-top box from before set-top boxes, and dating from the moment around five or six decades ago when that country expanded its TV broadcast network to include the UHF bands. If your TV was VHF it couldn’t receive the new channels, and this box was the answer to connecting your UHF antenna to that old TV.