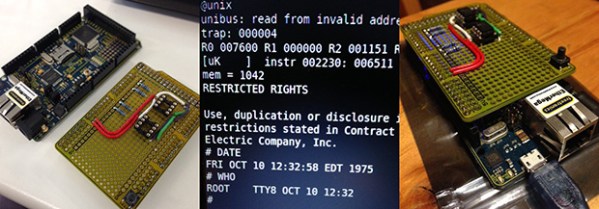

[Quinn] has been on Veronica, her 6502-based computer for quite a while now, but until very recently it’s been more of an embedded project rather than a fully functional computer. Writing software for Veronica on Veronica has been the goal from the start, and finally [Quinn] can write code from a ROM monitor.

In its most basic state, a ROM monitor is an extremely simple piece of software. It resides on the ROM of a computer and is the first thing the computer loads on booting, allowing the user to inspect, read, and write to memory locations, writing code in hex, and running it straight from the monitor.

To write the ROM monitor (and a few other programs), [Quinn] is using the awesome cc65 6502 C compiler. This comes with a whole bunch of macros that make it easy to read keyboard input, shove bits into her AVR GPU, and writing to memory. The monitor program is loaded onto her ROM chip which is automatically read every time the reset button is pressed.

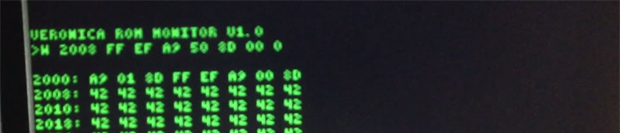

In the video below, you can see [Quinn] writing a few bits to address $2000 that tell the CPU to output ASCII characters to the display. It’s not much, but it’s the first time [Quinn] has written code for Veronica on Veronica, and should prove to be the beginning of a very interesting system.