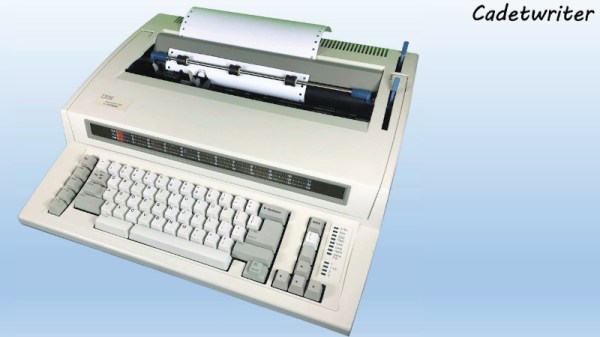

It may come as little surprise to find that Hackaday does not often play host to typewriter projects. While these iconic machines have their own particular charm, they generally don’t allow for much in the way of hardware modification. But then the IBM Wheelwriter 1000 isn’t exactly a traditional typewriter, which made its recent conversion to a fully functional computer terminal possible.

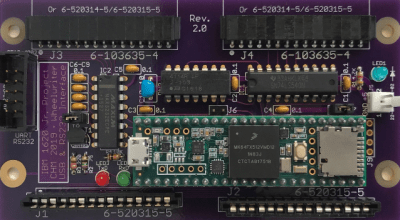

A product of the Computer History Museum’s [IBM 1620 Jr. Team], this modification takes the form of a serial interface board that can be built at home and installed into the Wheelwriter. The board allows the vintage electronic typewriter to speak RS-232 and USB, so it can be connected to whatever vintage (or not so vintage) computer you can imagine. The documentation for the project gives a rough cost of $150, though that does assume you’ve already got a Wheelwriter 1000 kicking around.

A product of the Computer History Museum’s [IBM 1620 Jr. Team], this modification takes the form of a serial interface board that can be built at home and installed into the Wheelwriter. The board allows the vintage electronic typewriter to speak RS-232 and USB, so it can be connected to whatever vintage (or not so vintage) computer you can imagine. The documentation for the project gives a rough cost of $150, though that does assume you’ve already got a Wheelwriter 1000 kicking around.

The GitHub repository includes everything you need to create your own board, and there’s even a highly detailed installation guide that goes over the case modifications necessary to get the new hardware installed. It also explains that you’ll want to get a new keycap set for your Wheelwriter if you perform this modification, as the original board doesn’t have all of the ASCII characters.

So why adapt an old electric typewriter to function as a teletype? As explained by the [IBM 1620 Jr. Team], there are projects out there looking to recreate authentic 1960s-era computing experiences that need a (relatively) affordable paper terminal. The originals are too rare to use in modern recreations, but with their adapter board, these slightly less archaic input devices can be used in their place.

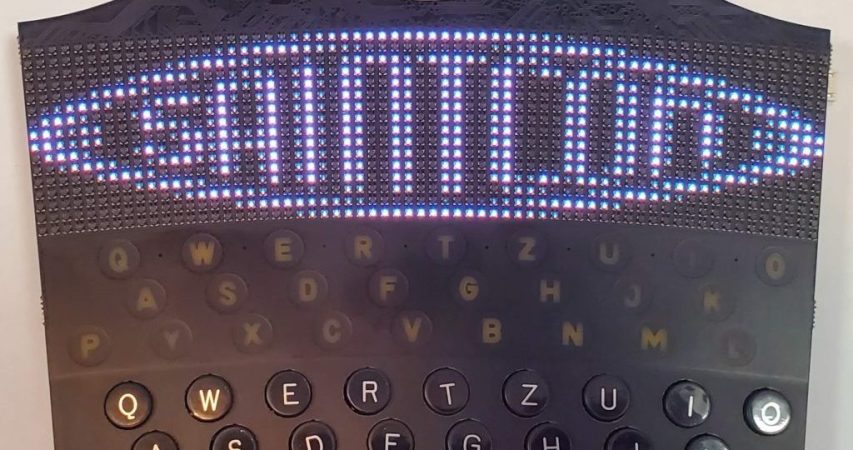

Once you’ve built your new teletype, or in the somewhat unlikely event you already have one at the ready, we’ve seen a couple of projects that you might be interested in to put it to use.