Eat more fruit, exercise more, drink more fluids; early January is traditionally the time to implement New Year’s resolutions. Most of the common ones simply require willpower, but if it’s staying hydrated that you’re targeting, then some help is available. [Pepijn de Vos] designed a LEGO cup holder and an accompanying desktop app that tell you exactly how much water you’ve had so far, making it easier to get to those eight glasses a day.

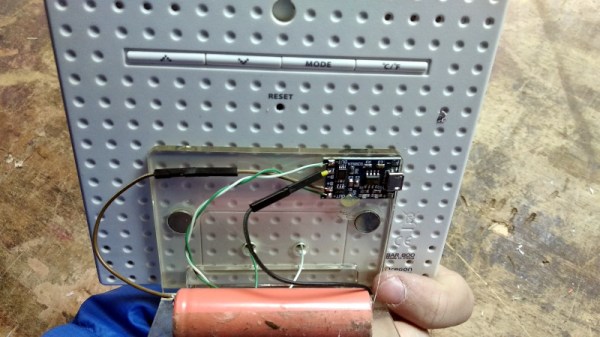

The basic idea is simple: the cup holder contains a load cell that senses the weight of your drinking vessel. If the weight decreases, then a message is sent to your PC detailing the amount lost. If the weight increases, then the glass must have been refilled and the previous weight is disregarded. This way, the app simply needs to add up all the amounts reported, without having to compensate for the weight of the empty glass.

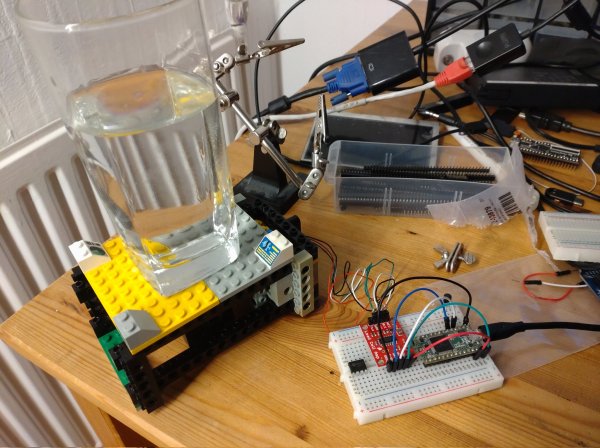

The tricky bit was integrating a load cell into the LEGO structure. It required some fiddling with Flex System hoses to ensure the platform’s weight rested only on the load cell, while still being stable enough to safely hold a full glass of water. The load cell is read out through an amplifier and A/D converter, while the USB communication is handled by a Teensy 3.

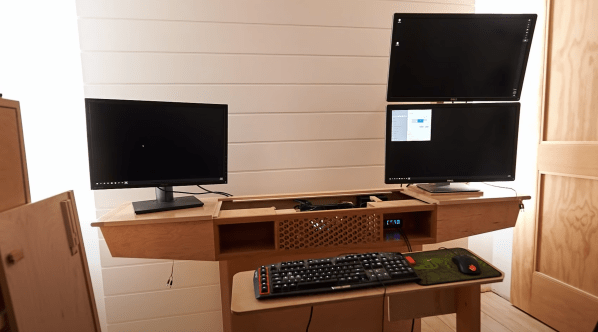

[Pepijn] modified an existing GNOME desktop widget to display a cup icon and the total volume consumed, which seems to work pretty smoothly judging from the video embedded below. All the code and even a complete set of LEGO build instructions are available on the project’s Github page. If simply monitoring your fluid intake isn’t enough of a nudge for you, then check out this device that floods your desk if you don’t drink enough.

Continue reading “LEGO Cup Holder Helps You To Stay Hydrated”