Every tech monopoly has their own proprietary smart home standard; how better to lock in your customers than to literally build a particular solution into their homes? Among the these players Apple is traditionally regarded as the most secretive, a title it has earned with decades of closed standards and proprietary solutions. This reputation is becoming progressively less deserved when it comes to HomeKit, their smart home gadget connectivity solution. In 2017 they took a big step forward and removed the need for a separate authentication chip in order to interact with HomeKit. Last week they took another and released a big chunk of their HomeKit Accessory Development Kit (ADK) as well. If you’re surprised not to have heard sooner, that might be because it was combined the the even bigger news about Apple, Amazon, the Zigbee Alliance, and more working together on more open, interoperable home IoT standards. Check back in 2030 to see how that is shaping up.

“The HomeKit ADK implements key components of the HomeKit Accessory Protocol (HAP), which embodies the core principles Apple brings to smart home technology: security, privacy, and reliability.”

– A descriptive gem from the README

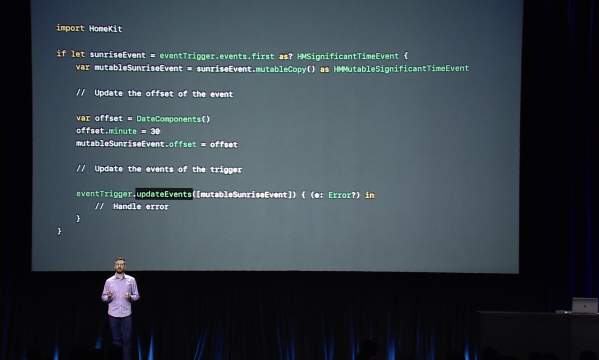

Apple’s previous loosening-of-restrictions allowed people to begin building devices which could interact natively with their iOS devices without requiring a specific Apple-sold “auth chip” to authenticate them. This meant existing commercial devices could become HomeKit enabled with an OTA, and hobbyists could interact in sanctioned, non-hacky ways. Part of this was a release of the (non-commercial) HomeKit specification itself, which is available here (with Apple developer sign in, and license agreement).

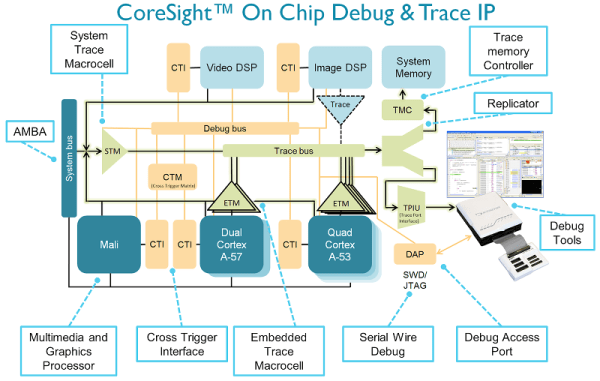

Despite many breathless mentions in the press release it’s hard to tell what the ADK actually is. The README and documentation directory are devoid of answers, but spelunking through the rest of the GitHub repo gives us an idea. It consists of two primary parts, the HomeKit Accessory Protocol itself and the Platform Abstraction Layer. Together the HAP implements HomeKit itself, and the PAL is the wrapper that lets you plug it into a new system. It’s quite a meaty piece of software; the HAP’s main header is a grueling 4500 lines long, and it doesn’t take much searching to find some fear-inspiring 50 line preprocessor macros. This is a great start, but frankly we think it will take significantly more documentation to make the ADK accessible to all.

If it wasn’t obvious, most of the tools above are carefully licensed by Apple and intended for non-commercial use. While we absolutely appreciate the chance to get our hands on interfaces like this, we’re sure many will quibble over if this really counts as “open source” or not (it’s licensed as Apache 2.0). We’ll leave that for you in the comments.