Building a Hackintosh – a non-Apple computer running MacOS – has been a favorite pastime of hackers ever since Apple made the switch from PowerPC to Intel hardware. Though usually built from commodity PC parts, some have successfully installed Apple’s OS onto various kinds of Intel-based single-board computers. [iketsj] used such a board to build a cute little Hackintosh, and apparently decided that if he was going to imitate Apple’s hardware, he might as well take some clues from their industrial design. The result can be seen in the video (embedded below) where [Ike] demonstrates a tiny iMac-like device with a 5″ LCD screen.

The brains of this cute little all-in-one are a Lattepanda, which is a compact board containing an Intel CPU, a few GB of RAM and lots of I/O interfaces. [Ike] completed it with a 256 GB SSD, a WiFi/Bluetooth adapter and the aforementioned LCD, which displays 800×480 pixels and receives its image through the mainboard’s HDMI interface.

The case is a 3D-printed design that vaguely resembles a miniaturized iMac all-in-one computer. The back contains openings for a couple of USB connectors, a 3.5 mm headphone jack and even an Ethernet port for serious networking. A pair of speakers is neatly tucked away below the display, enabling stereo sound even without headphones.

The computer boots up MacOS Monterey just like a real iMac would, just with a much smaller display. [Ike] is the first to admit that it’s not the most practical thing in the world, but that he would go out and use it in a coffee shop “just for the lulz”. And we agree that’s a great reason to take your hacks outside.

[Ike] built a portable Hackintosh before, and we’ve seen some pretty impressive MacOS builds, like this Mini iMac G4, a beautiful Mac Pro replica in a trash can, and even a hackintosh built inside an actual Mac Pro case.

Continue reading “Cute Little IMac Clone Runs MacOS On A Tiny Screen”

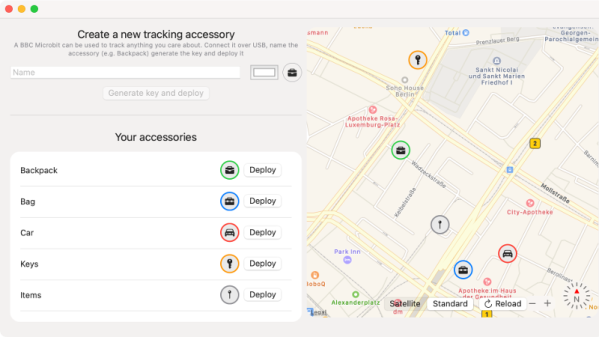

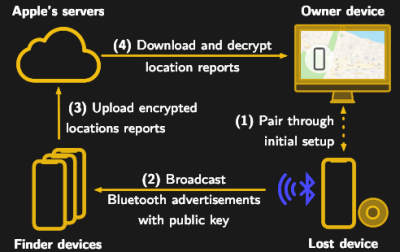

Somewhat ironically, while OpenHaystack allows you to track non-Apple devices on the Find Me tracking network, you will need a Mac computer to actually see where your device is. The team’s software requires a computer running macOS 11 (Big Sur) to run, and judging by the fact it integrates with Apple Mail to pull the tracking data through a private API, we’re going to assume this isn’t something that can easily be recreated in a platform-agnostic way.

Somewhat ironically, while OpenHaystack allows you to track non-Apple devices on the Find Me tracking network, you will need a Mac computer to actually see where your device is. The team’s software requires a computer running macOS 11 (Big Sur) to run, and judging by the fact it integrates with Apple Mail to pull the tracking data through a private API, we’re going to assume this isn’t something that can easily be recreated in a platform-agnostic way.