Want a little heads-up before walking into a potentially dangerous radioactive area? Sure, we all do. But the typical surplus Civil Defense Geiger counter is just too bulky to fit into the sleek, modern every-day carry of the smartphone age. So why not slim down your first line of defense against achieving mutant status with this tiny Geiger counter (Facebook)?

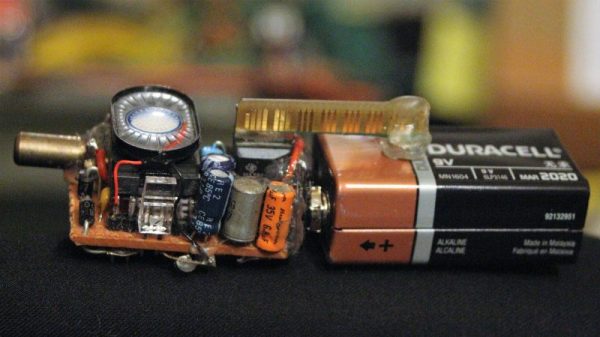

We jest about the use cases for a personal-sized Geiger counter, as [Ian King]’s inspiration for this miniaturized build was based more on a fascination with quantifying the unseen world around us. Details are thin in his post, but [Ian] kindly shared the backstory for this build with us. Working on a budget and mostly with spare parts, the big outlay in the BOM was $20 for a Soviet-era SBM-10 tube, itself a marvel of miniaturization. While waiting the two months needed for the tube to arrive, [Ian] whipped up a perf board circuit with a simple oscillator and a CFL transformer to provide the 400 volts needed for the tube. The whole circuit, complete with tiny speaker and an LED to indicate pulses, sits neatly on top of a 9-volt battery. The video below shows it in action with a test source.

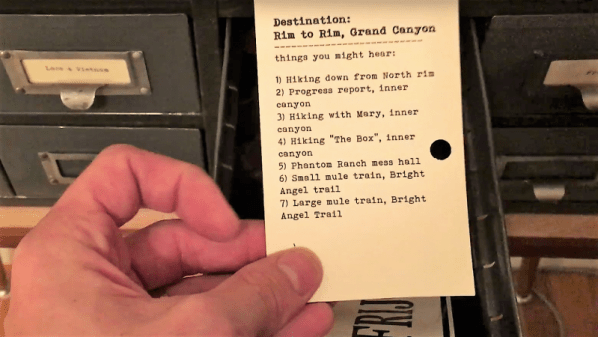

Geiger counters are not exactly rare projects on Hackaday, and with good reason. Take a look at this no-solder scrap bin counter or this traveling GPS Geiger counter built dead-bug style.

Continue reading “Fun-Size Geiger Counter Sits Atop A 9-Volt Battery”

His design is based around a

His design is based around a