Sometimes when you need a component, the best way to get it is by building it yourself. [North Carolina Prepper] did just that, creating his own trombone-style variable capacitor by stretching some aluminium beverage cans.

The requirement was for a 26 pF to 472 pF capactitor, for a radio transmitting from 7 MHz to 30MHz. The concept was to use two beverage cans, one sliding inside the other, as a capacitor, with an insulating material in between.

To achieve this, a cheap exhaust-pipe expanding tool was used to stretch a regular can to the point where it would readily slide over an unmodified can, plus some additional gap to allow for a plastic insulating sheet in between. Annealing the can is important to stop it tearing up, but fundamentally, it’s a straightforward process.

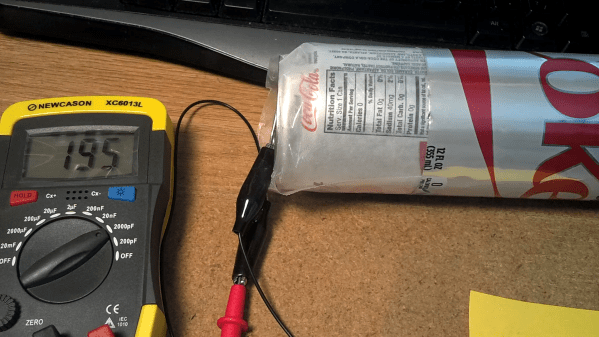

The resulting trombone capacitor can readily be slid in and out to change its capacitance. The build as seen here achieved 33 pF to 690 pF without too much hassle, not far off the specs [North Carolina Prepper] was shooting for.

Radio hams are very creative at building their own equipment, especially when it comes to variable capacitors. Video after the break.

Continue reading “Making Variable Capacitors By Stretching Aluminium Cans”