We’ve seen a great many Arduino synthesizer projects over the years. We love to see a single Arduino bleeping out some monophonic notes. From there, many hackers catch the bug and the sky is truly the limit. [Kevin] is one such hacker who now has an Arduino orchestra capable of playing all seven movements of Gustav Holst’s Planets Suite.

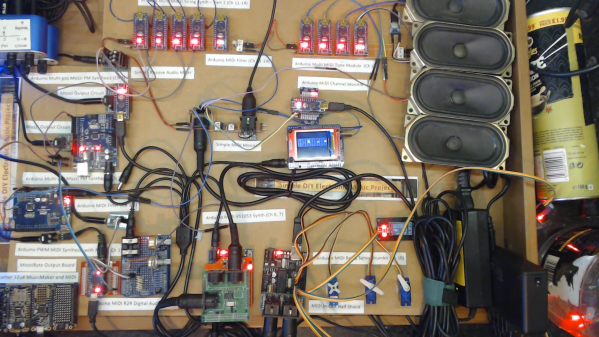

The performers are not human beings with expensive instruments, but simple microcontrollers running code hewn by [Kevin’s] own fingertips. The full orchestra consists of 11 Arduino Nanos, 6 Arduino Unos, 1 Arduino Pro Mini, 1 Adafruit Feather 32u4, and finally, a Raspberry Pi.

Different synths handle different parts of the performance. There are General MIDI synths on harp and bass, an FM synth handling wind and horn sections, and a bunch of relays and servos serving as the percussive section. The whole orchestra comes together to do a remarkable, yet lo-fi, rendition of the whole orchestral work.

While it’s unlikely to win any classical music awards, it’s a charming recreation of a classical piece and it’s all the more interesting coming from so many disparate parts working together. It’s an entirely different experience than simply listening to a MIDI track playing on a set of headphones.

We’d love to see some kind of hacker convention run a contest for the best hardware orchestra. It could become a kind of demoscene contest all its own. In the meantime, scope one of [Kevin’s] earlier projects on the way to this one – 12 Arduinos singing Star Wars tracks all together. Video after the break.

Continue reading “Arduino Orchestra Plays The Planets Suite”

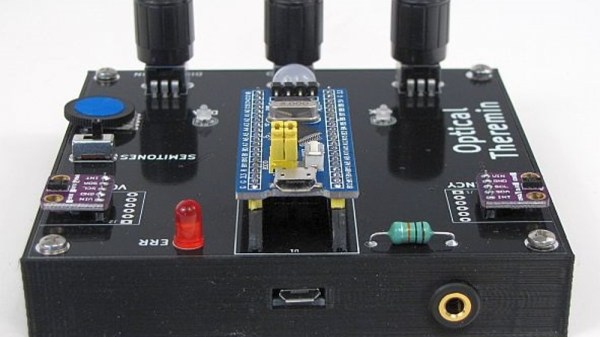

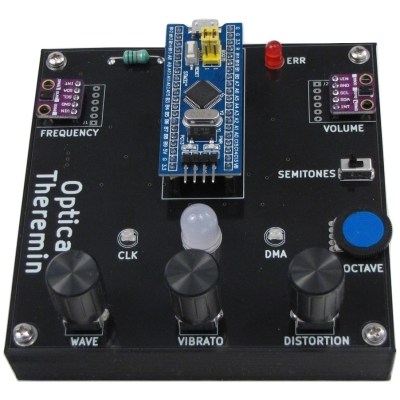

The design is based on a ‘

The design is based on a ‘