We all know that solderless breadboards have their limitations. All that stray capacitance can play hell with circuits, especially high-speed stuff, but they’re so darn useful that avoiding them in favor of some other prototyping method can be really hard. So we often just forge ahead, plugging in our parts and hoping for the best

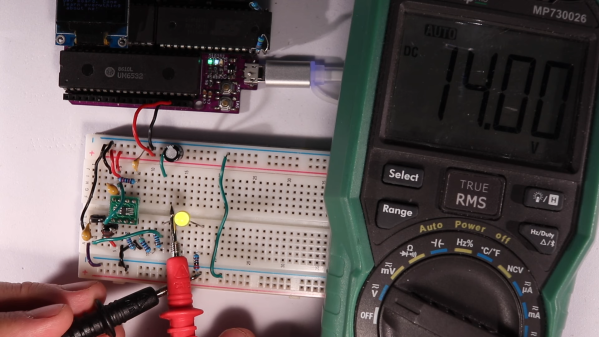

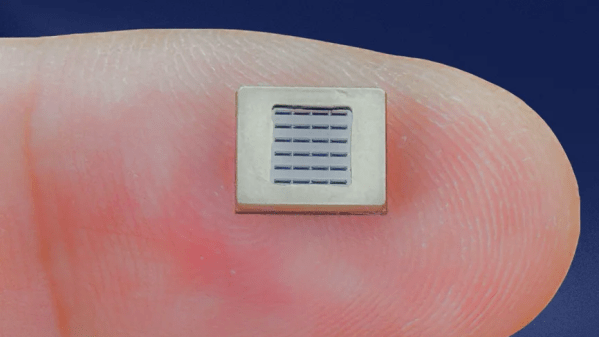

A recent veteran of the breadboard battle is [Anders Nielsen], who kicked off a new project by prototyping this high-voltage boost converter on a breadboard, with mixed results. The project is a scratch-built programmer for old-school ROM chips, a task normally farmed out to a dedicated programmer, but where’s the sport in that? Besides, this is the future, and generating the 12 to 14 volts needed should be a snap. And it would be, except for the fact that his chosen chip, a MIC2288 switching boost regulator, is only available in an SMD package. Getting the chip and a few other SMD support components onto breadboard-compatible breakouts proved to be challenging, and getting it working once it was there was even more work.

A lot of the trouble was down to simple breadboarding errors, but the big problem was the input capacitance, which [Anders] had to fiddle with quite a bit to get the converter to 14 volts. The current maxes out at about 25 mA before the voltage starts dropping, which just might be enough to burn those old chips, so we’ll call this a provisional win and see what happens when he builds the rest of the programmer.

[Anders]’ experience here raises a good question: what’s the best way to prototype using fussy SMD components? PCBs are cheap enough that it’s tempting to go straight to one, but swapping parts in and out like he had to do here to get everything just right would be much harder that way. We’re not sure we know the answer, but we’re pretty sure we’ll hear your thoughts on that in the comments section.

Continue reading “Switching Converter For EEPROM Programmer Taxes Solderless Breadboard”