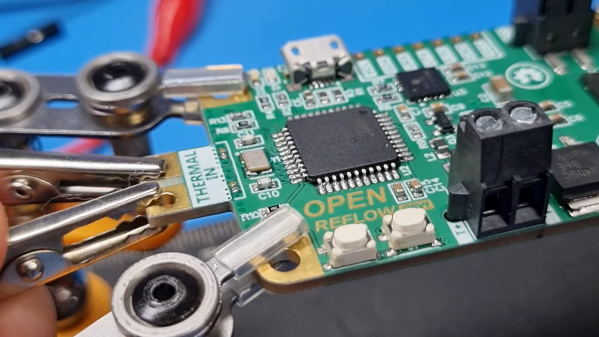

Lithium batteries have, nearly single-handedly, ushered in the era of the electric car, as well as battery energy storage of grid power and plenty of other technological advances not possible with older battery chemistries. There’s just one major downside: these lithium cells can be extremely finicky. If you’re adding one to your own project you’ll have to be extremely careful to treat them exactly how they are designed to be treated using something like this boilerplate battery protection circuit created by [DIY GUY Chris].

The circuit is based around the TP4056 integrated circuit, which handles the charging of a single lithium cell — in this design using supplied power from a USB port. The circuit is able to charge a cell based on the cell’s current charge state, temperature, and a model of the cell. It’s also paired with a DW01A chip which protects the cell from various undesirable conditions such as over-current, overcharge, and over-voltage.

The best thing about this design isn’t the design itself, but that [DIY GUY Chris] built the circuit schematic specifically to be easily copied into PCB designs for other projects, which means that lithium batteries can more easily be integrated directly into his other builds. Be sure to check out our primer on how to deal with lithium batteries before trying one of your own designs, though.

Continue reading “Copy And Paste Lithium Battery Protection”