Have you ever looked at a small development board like an Arduino or an ESP8266 board and thought you’d like one with just a few different features? Well, [Kai] has put out a fantastic guide on how to make an RP2040 dev board that’s all your own.

Development boards are super useful for prototyping a project, and some are quite simple, but there’s often some hidden complexity that needs to be considered before making your own. The RP2040 is a great chip to start your dev-board development journey, thanks to its excellent documentation and affordable components. [Kai] started this project using KiCad, which has all the features needed to go from schematics to final PCB Gerber files. In the write-up, [Kai] goes over how to implement USB-C in your design and how to add flash memory to your board, providing a place for your program to live. Once the crystal oscillator circuit is defined, decoupling capacitors added, and the GPIO pins you want to use are defined, it’s time to move to the PCB layout.

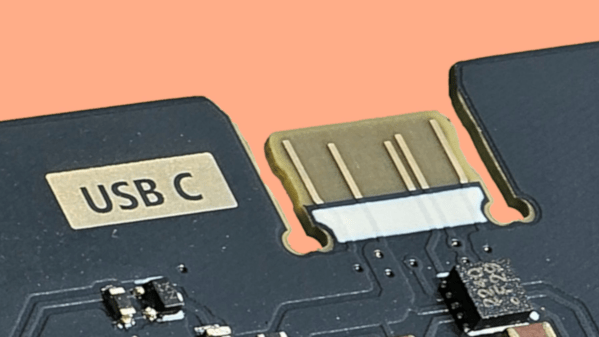

In the PCB design, it starts with an outside-in approach, first defining the board size, then adding the pins that sit along the edges of that board, followed by the USB connector, and then moving on to the internal components. Some components, such as the crystal oscillator, need to be placed near the RP2040 chip, and the same goes for some of the decoupling capacitors. There is a list of good practices around routing traces that [Kai] included for best results, which are useful to keep in mind once you have this many connections in a tight space. Not all traces are the same; for instance, the USB-C signal lines are a differential pair where it’s important that D+ and D- are close to the same length.

Finally, there is a walk-through on the steps needed to have your boards not only made at a board house but also assembled there if you choose to do so. Thanks [Kai] for taking the time to lay out the entire process for others to learn from; we look forward to seeing future dev-board designs. Be sure to check out some of our other awesome RP2040 projects.