Make the move to a split keyboard and the first thing you’ll notice is that you have all this real estate between the two halves. (Well, as long as you’re doing it right). This is the perfect place to keep your cat, your coffee cup, or in [Jacek]’s case, your fantastic DIY trackball mouse.

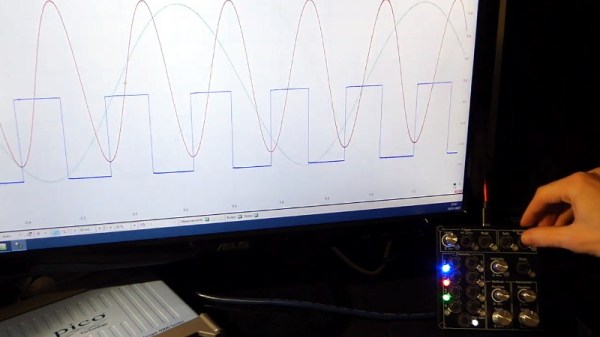

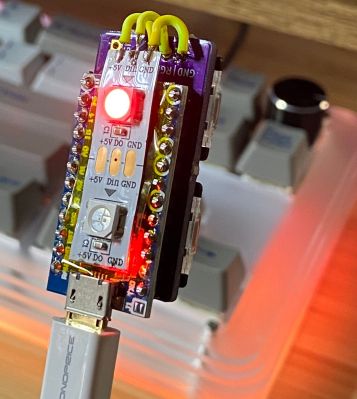

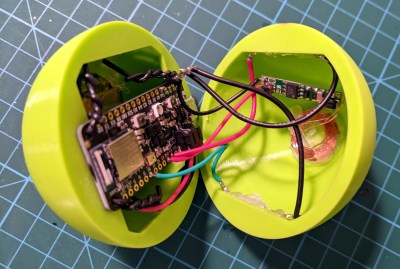

Don’t be fooled by the orange plastic base — all the electronics are rolled up inside that big sexy ball, which [Jacek] printed in two halves and glued together. Inside the ball there’s an Adafruit Feather nRF52840 Sense, which has an onboard accelerometer, gyroscope, and magnetometer. As you’ll see in the video after the break, the Feather takes readings from these and applies a sensor-fusing algorithm to determine the ball’s orientation in 3D space before sending its position to the computer. To send the click events, [Jacek] baked some mouse buttons into the keyboard’s firmware. Among the other Feather sensors is a PDM MEMS microphone, so detecting taps on the ball and translating them to clicks is not out of the question for a future version.

Don’t be fooled by the orange plastic base — all the electronics are rolled up inside that big sexy ball, which [Jacek] printed in two halves and glued together. Inside the ball there’s an Adafruit Feather nRF52840 Sense, which has an onboard accelerometer, gyroscope, and magnetometer. As you’ll see in the video after the break, the Feather takes readings from these and applies a sensor-fusing algorithm to determine the ball’s orientation in 3D space before sending its position to the computer. To send the click events, [Jacek] baked some mouse buttons into the keyboard’s firmware. Among the other Feather sensors is a PDM MEMS microphone, so detecting taps on the ball and translating them to clicks is not out of the question for a future version.

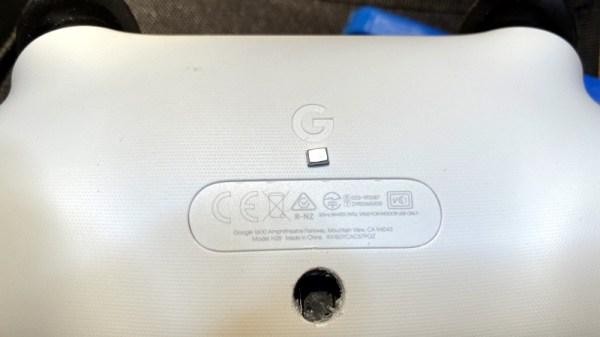

Here comes the really clever part: there are two reed switches inside the ball. One is used as a power switch, and the other is for setting the ‘up’ direction of the trackball. The ball charges wirelessly in a 3D printed base, which also has a small neodymium magnet for activating the reed switches. Check out the demo after the break, which shows [Jacek] putting the trackball through its paces on a mouse accuracy testing program.

If you prefer your DIY trackballs to be more standard looking, click on over to the Ploopy project.