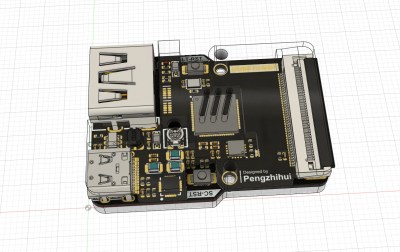

It seems that few features of a consumer electronic product will generate as much rancour as a mobile phone charger socket. For those of us with Android phones, the world has slowly been moving over the last few years from micro-USB to USB-C, while iPhone users regard their Lightning connector as the ultimate in connectivity. Get a set of different phone owners together and this can become a full-on feud, as micro-USB owners complain that nobody has a handy charging cable any more, USB-C owners become smug bores, and Apple owners do what they’ve always done and pretend that Steve Jobs invented USB. Throwing a flaming torch into this incendiary mix is the European Union, which is proposing to mandate the use of USB-C on all phones sold in its 27 member nations with the aim of reducing considerably the quantity of e-waste generated.

Minor annoyances over having to carry an extra micro-USB cable for an oddball device aside, we can’t find any reason not to applaud this move, because USB-C is a connector born of several decades of USB evolution and brings with it not only the reversible plug but also the enhanced power delivery standards that enable fast charging no matter whose USB-PD charger you are using. Mandating USB-C will put an end to needlessly overpriced proprietary cables, and bring eventual unity to a fractured world. Continue reading “Showdown Time For Non-Standard Chargers In Europe”