We generally cast a skeptical eye at projects that claim some kind of superlative. If you go on about the “World’s Smallest” widget, the chances are pretty good that someone will point to a yet smaller version of the same thing. But in the case of what’s touted as “The world’s smallest vector monitor”, we’re willing to take that chance.

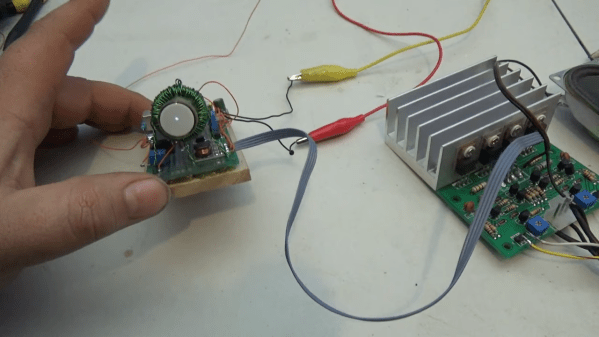

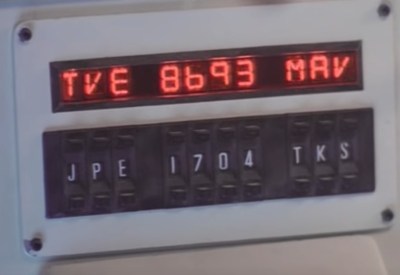

If you’ve seen any of [Arcade Jason]’s projects before, you’ll no doubt have noticed his abiding affection for vector displays. We’re OK with that; after all, many of the best machines from the Golden Age of arcade games such as Asteroids and Tempest were based on vector graphics. None so small as the current work, though, based as it is on the CRT from an old camcorder’s viewfinder. The tube appears to be about 3/4″ (19 mm) in diameter, and while it still had some of its original circuitry, the deflection coils had to be removed. In their place, [Jason] used a ferrite toroid with two windings, one for vertical and one for horizontal. Those were driven directly by a two-channel push-pull audio amplifier to make patterns on the screen. Skip to 15:30 in the video below to see the display playing [Jerobeam Fenderson]’s “Oscilloscope Music”.

As much as we’d love to see a tiny game of Battlezone played on the diminutive display, there’s only so much it can do. Maybe an analog version of this adorable digital oscilloscope would be possible?

Continue reading “Camcorder Viewfinder Converted To Diminutive Vector Display”