When your publication is about to hold a major event on your side of the world, and there will be a bring-a-hack, you abruptly realise that you have to do just that. Bring a hack. With the Hackaday London Unconference in the works this was the problem I faced, and I’d run out of time to put together an amazing PCB with beautiful artwork and software-driven functionality to amuse and delight other attendees. It was time to come up with something that would gain me a few Brownie points while remaining within the time I had at my disposal alongside my Hackaday work.

Since I am a radio enthusiast at heart, I came up with the idea of a badge that the curious would identify as an FM transmitter before tuning a portable radio to the frequency on its display and listening to what it was sending. The joke would be of course that they would end up listening to a chiptune version of [Rick Astley]’s “Never gonna give you up”, so yes, it was going to be a radio Rickroll.

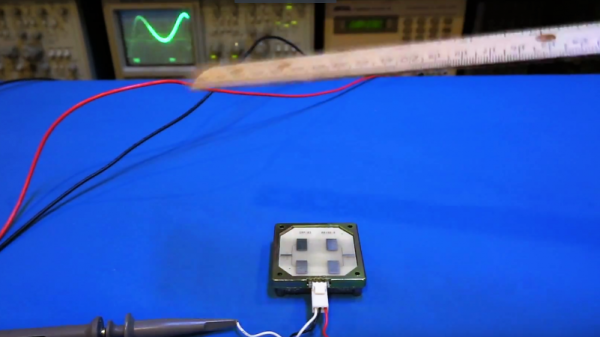

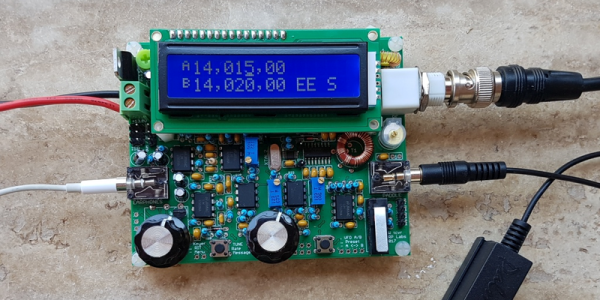

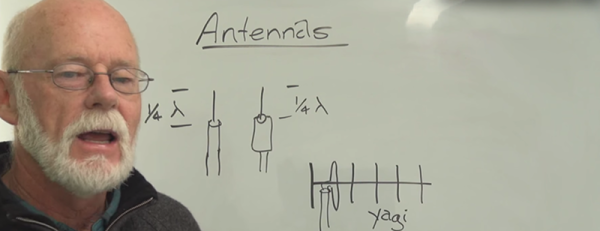

I evaluated a few options, and ended up with a Raspberry Pi Zero as an MP3 player through its PWM lines, feeding through a simple RC low-pass filter into a commercial super-low-power FM transmitter module of the type you can legally use with an iPod or similar to listen on a car radio. To give it a little bit of individuality I gave the module an antenna, a fractal design made from a quarter wavelength of galvanised fence wire with a cut-off pin from a broken British mains plug as a terminal. The whole I enclosed in a surplus 8mm video cassette case with holes Dremmeled for cables, with the FM module using its own little cell and the Pi powered from a mobile phone booster battery clipped to its back. This probably gave me a transmitted field strength above what it should have been, but the power of those modules is so low that I am guessing the sin against the radio spectrum must have been minor.

At the event, a lot of people were intrigued by the badge, and a few of them were even Rickrolled by it. But for me the most interesting aspect lay not in the badge itself but in its components. First I looked at making a PCB with MP3 and radio chips, but decided against it when the budget edged towards £20 ($27). Then I looked at a Raspberry Pi running PiFM as an all-in-one solution with a little display HAT, but yet again ran out of budget. An MP3 module, Arduino clone, and display similarly became too expensive. Displays, surprisingly, are dear. So my cheapest option became a consumer FM module at £2.50 ($3.37) which already had an LCD display, and a little £5 ($6.74) computer running Linux that was far more powerful than the job in hand demanded. These economics would have been markedly different had I been manufacturing a million badges, but made a mockery of the notion that the simplest MCU and MP3 module would also be the cheapest.

Rickrolling never gets old, it seems, but evidently it has. Its heyday in Hackaday projects like this prank IR repeater seems to have been in 2012.

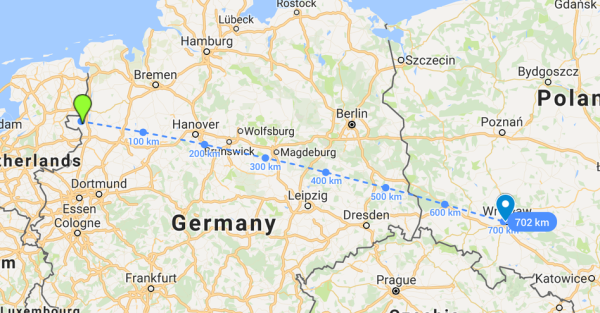

A couple of weeks ago at an alternative society festival in the Netherlands, a balloon was launched with a LoRaWAN payload on board that was later found to have

A couple of weeks ago at an alternative society festival in the Netherlands, a balloon was launched with a LoRaWAN payload on board that was later found to have