If one has a multi-material printer there are more options than simply printing in different colors of the same filament. [Thomas Sanladerer] explores combinations of different filaments in a fantastic article that covers not just which materials make good removable support interfaces, but also which ones stick to each other well enough together to make a multi-material print feasible. He tested an array of PLA, PETG, ASA, ABS, and Flex filaments with each in both top (printed object) and bottom (support) roles.

People had already discovered that PETG and PLA make pretty good support for each other. [Thomas] expands on this to demonstrate that PLA doesn’t really stick very well to anything but itself, and PETG by contrast sticks really well to just about anything other than PLA.

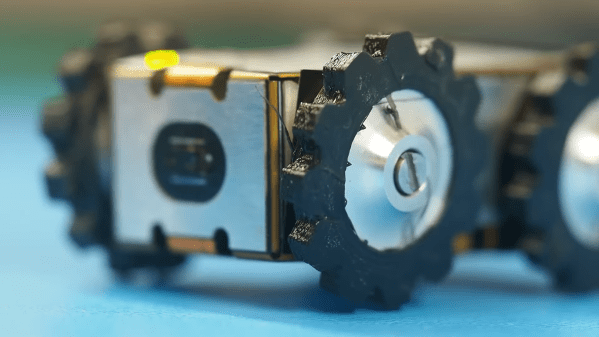

One mild surprise was that flexible filament conforms very well to PLA, but doesn’t truly stick to it. Flex can be peeled away from PLA without too much trouble, leaving a very nice finish. That means using flex filament as a zero-clearance support interface — that is to say, the layer between the support structure and the PLA print — seems like it has potential.

Flex and PETG by contrast pretty much permanently weld themselves together, which means that making something like a box out of PETG with a little living hinge section out of flex would be doable without adhesives or fasteners. Ditto for giving a PETG object a grippy base. [Thomas] notes that flexible filaments all have different formulations, but broadly speaking they behave similarly enough in terms of what they stick to.

[Thomas] leaves us with some tips that are worth keeping in mind when it comes to supported models. One is that supports can leave tiny bits of material on the model, so try to use same or similar colors for both support and model so there’s no visual blemish. Another tip is that PLA softens slightly in hot water, so if PLA supports are clinging stubbornly to a model printed in a higher-temperature material like PETG or ABS/ASA, use some hot water to make the job a little easier. The PLA will soften first, giving you an edge. Give the video below a watch to see for yourself how the combinations act.

Continue reading “Printing In Multi-material? Use These Filament Combos”

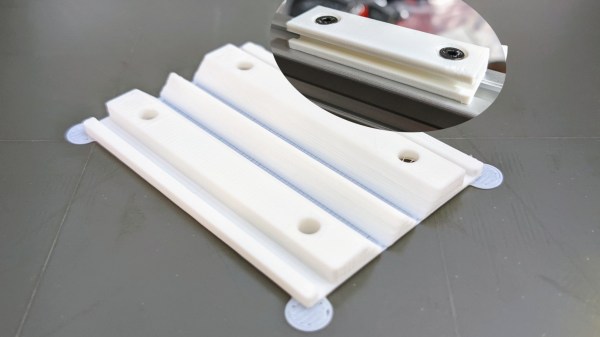

The example Chris provides is a Eurorack rail segment — due to the kind of overhangs required, you’d be inclined to print it vertically, taking a hit to the print time and introducing structural weaknesses. With this trick, you absolutely don’t have to! You can also go way further and 3D print a single-piece foldable

The example Chris provides is a Eurorack rail segment — due to the kind of overhangs required, you’d be inclined to print it vertically, taking a hit to the print time and introducing structural weaknesses. With this trick, you absolutely don’t have to! You can also go way further and 3D print a single-piece foldable