If you have ever browsed an amateur radio magazine you could be forgiven for receiving the impression that it is a pursuit exclusively for the wealthy. Wall-to-wall adverts for very large and shiny transceivers with hefty price tags abound, and every photograph of someone’s shack seems to sport a stack of them.

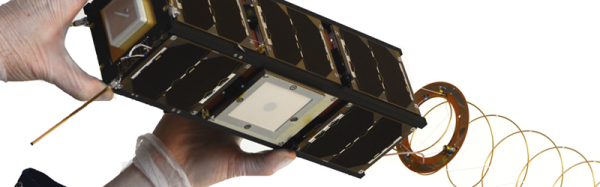

Of course, this is only part of the story. Amateur radio is and always has been an astonishingly diverse interest, and away from the world of shiny adverts you’ll find a lot of much more interesting devices. A lot of radio amateurs still design and build their own equipment, and the world of homebrew radio is forever producing new ideas.

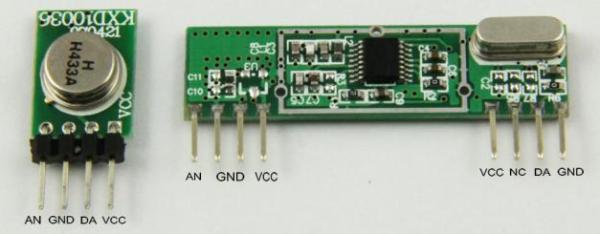

One such project came to our attention recently, the Minima, an all-band HF SSB transceiver. It’s an interesting device for several reasons, it uses readily available components, it’s an impressively simple design, and it should cost under $100 to build. This might sound a little far-fetched, were it not from the bench of [Ashhar Farhan, VU2ESE], whose similarly minimalist BITX single band SSB transceiver set a new standard for accessible SSB construction a few years ago.

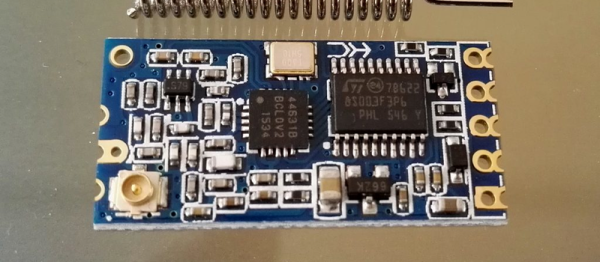

The circuit shares some similarities with the tried-and-tested BITX, using bi-directional amplifier building blocks. The mixers are now FETs rather than diodes, the intermediate frequency has moved from 9MHz to 20MHz, and the local oscillator is now an Arduino-controlled clock generator. The whole thing is designed to be built dead-bug-style if necessary, and two prototypes have been built. We’d expect this design to follow a similar evolution to the BITX, with the global community of radio amateurs contributing performance modifications, and no doubt with some kit suppliers producing PCBs and kits. We think this can only be a good thing, and look forward to covering some of the results.

We’ve featured [Ashhar]’s work here at Hackaday before, when we covered a BITX build. if you’re left wondering what this amateur radio business is all about, we suggest you have a read of [Bill Meara]’s guest post on the subject.

Thanks [Seebach] for the tip.

![Can these logos really be trusted? By Moppet65535 (Own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0], via Wikimedia Commons](https://hackaday.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/fcc-ce-logos.jpg?w=400)