Picture this: It’s the end of the year, and a few hardy souls gather in a hackerspace to enjoy a bit of seasonal food and hang out. Conversation turns to the Flipper Zero, and aspects of its design, and one of the parts we end up talking about is its built-in 125 kHz RFID reader.

It’s a surprisingly complex circuit with a lot of filter components and a mild mystery surrounding the use of a GPIO to pulse the receive side of its detector through a capacitor. One thing led to another as we figured out how it worked, and as part of the jolity we ended up with one member making a simple RFID reader on the bench.

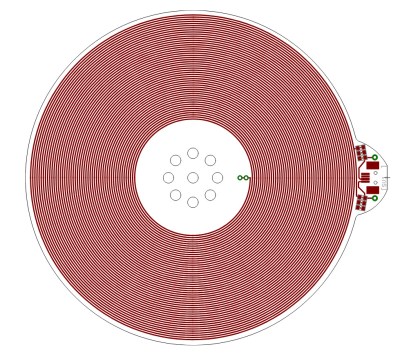

Just a signal generator making a 125 kHz square wave, coupled to a two transistor buffer pumping a tuned circuit. The tuned circuit is the coil scavenged from an old RFID card, and the capacitor is picked for resonance in roughly the right place. We were rewarded with the serial bitstream overlaying the carrier on our ‘scope, and had we added a filter and a comparator we could have resolved it with a microcontroller. My apologies, probably due to a few festive beers I failed to capture a picture of this momentous event. Continue reading “New Years Circuit Challenge: Make This RFID Circuit”