Amateur radio license exams typically have a question about the bandwidths taken up by various modulation types. The concept behind the question is pretty obvious — as guardians of the spectrum, operators really should know how much space each emission type occupies. As a result, the budding ham is left knowing that continuous wave (CW) signals take up a mere 150 Hertz of precious bandwidth.

But is that really the case? And what does the bandwidth of a CW signal even mean, anyway? To understand that, we turn to [Alan (W2AEW)] and his in-depth look at CW bandwidth. But first, one needs to see that CW signals are a bit special. To send Morse code, the transmitter is not generating a tone for the dits and dahs and modulating a carrier wave, rather, the “naked” carrier is just being turned on and off by the operator using the transmitter’s keyer. The audio tone you hear results from mixing the carrier wave with the output of a separate oscillator in the receiver to create a beat frequency in the audio range.

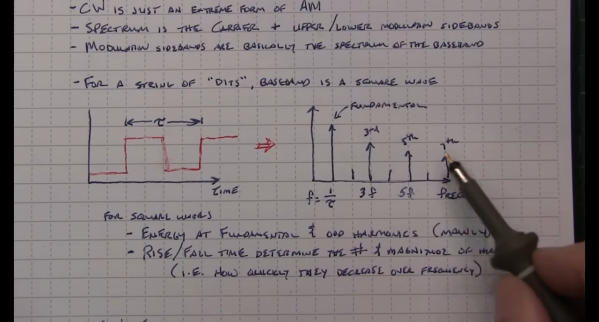

That seems to suggest that CW signals occupy zero bandwidth since no information is modulated onto the carrier. But as [Alan] explains, the action of keying the transmitter imposes a low-frequency square wave on the carrier, so the occupied bandwidth of the signal depends on how fast the operator is sending, as well as the RF rise and fall time. His demonstration starts with a signal generator modulating a 14 MHz RF signal with a simple square wave at a 50% duty cycle. By controlling the keying frequency, he mimics different code speeds from 15 to 40 words per minute, and his fancy scope measures the occupied bandwidth at each speed. He’s also able to change the rise and fall time of the square wave, which turns out to have a huge effect on bandwidth; the faster the rise-fall, the larger the bandwidth.

It’s a surprising result given the stock “150 Hertz” answer on the license exam; in fact, none of the scenarios [Allen] tested came close to that canonical figure. It’s another great example of the subtle but important details of radio that [Alan] specializes in explaining.

Continue reading “How Much Bandwidth Does CW Really Occupy?”