HF radios often use toroidal transformers and winding them is a rite of passage for many RF hackers. [David Casler, KE0OG] received a question about how they work and answered it in a recent video that you can see below.

Understanding how a conventional transformer works is reasonably simple, but toroids often seem mysterious because the thing that makes them beneficial is also what makes them confusing. The magnetic field for such a transformer is almost totally inside the “doughnut,” which means there is little interaction with the rest of the circuit, and the transformer can be very efficient.

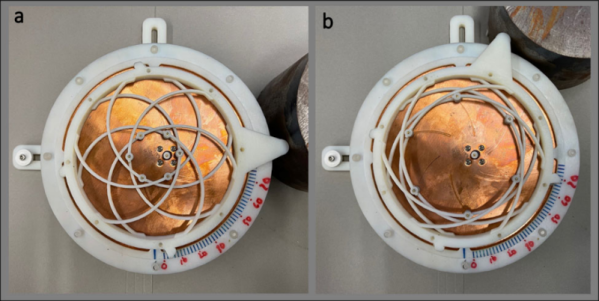

The toroid itself is made of special material. They are usually formed from powdered iron oxide mixed with other metals such as cobalt, copper, nickel, manganese, and zinc bound with some sort of non-conducting binder like an epoxy. Ferrite cores have relatively low permeability, low saturation flux density, and low Curie temperature. The powder also reduces the generation of eddy currents, a source of loss in transformers. Their biggest advantage is their high electrical resistivity, which helps reduce the generation of eddy currents.

If you haven’t worked through how these common little transformers work, [David]’s talk should help you get a grip on them. These aren’t just for RF. You sometimes see them in power supplies that need to be efficient, too. If you are too lazy to wind your own, there’s always help.