The LoRa radio protocol is well known to hardware hackers because of its Long Range (hence the name) but also its extremely low power use, making it a go-to for battery powered devices with tiny antennae. But what if the power wasn’t low, and the antenna not tiny? You might just bounce a LoRa message off the moon. But that’s not all.

The team that pulled off the LoRa Moonbounce consisted of folks from the European Space Agency, Lacuna Space, and the CA Muller Radio Astronomy Station Foundation which operates the Dwingeloo Radio Telescope. The Dwingeloo Radio Telescope is no stranger to Amateur Radio experiments, but this one was unique.

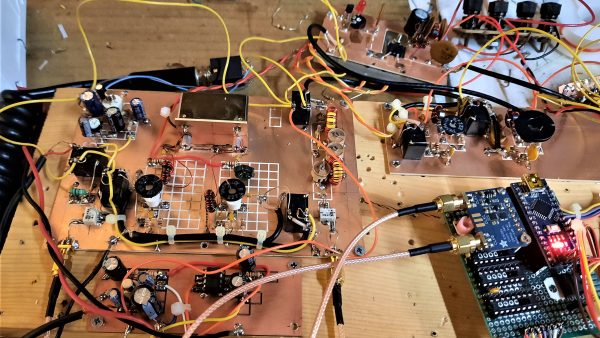

Operating in the 70 cm Amateur Radio band (430 MHz) meant that the LoRa signal was not limited to the low power signals allowed in the ISM bands. The team amplified the signal to 350 Watts, and then used the radio telescope’s 25 Meter dish to direct the transmission toward the moon.

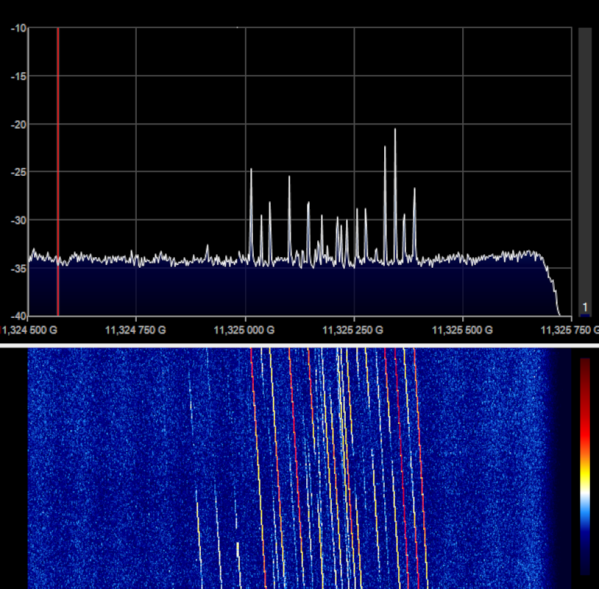

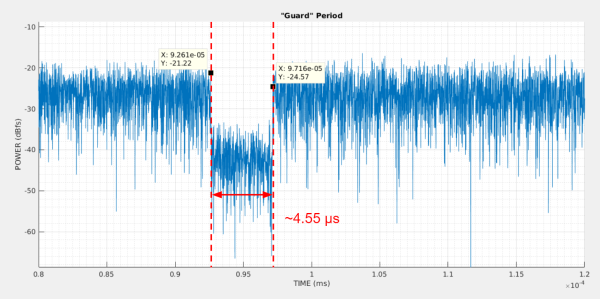

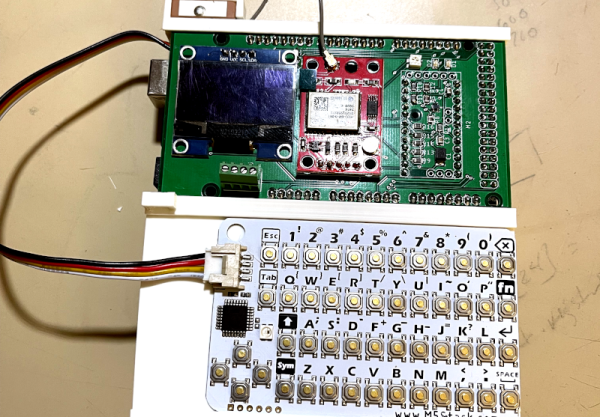

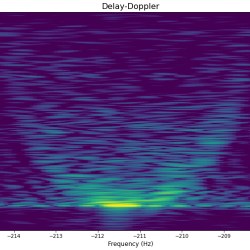

The result? Not only were they able to receive the reflected transmission using the same transceiver they modulated it with — an off the shelf IOT LoRa radio — but they also recorded the transmission with an SDR. By plotting frequency and doppler delay, the LoRa transmission was able to be used to get a radar image of the moon- a great dual purpose use that is noteworthy in and of itself.

LoRa is a versatile technology, and can even be used for tracking your High Altitude Balloon that’s returned to Terra Firma.