Little humans have a knack for throwing a wrench in the priorities of their parents. As anyone who’s ever had children will tell you, there’s nothing you wouldn’t do for them. If you ever needed evidence to this effect, just take a gander at the nearly year-long saga that chronicles the construction of an activity board [Michael Teeuw] built for his son, Enzo.

Whether you start at the beginning or skip to the end to see the final product, the documentation [Michael] has done for this project is really something to behold. From the early days of the project where he was still deciding on the overall look and feel, to the final programming of the Raspberry Pi powered user interface, every step of the process has been meticulously detailed and photographed.

Whether you start at the beginning or skip to the end to see the final product, the documentation [Michael] has done for this project is really something to behold. From the early days of the project where he was still deciding on the overall look and feel, to the final programming of the Raspberry Pi powered user interface, every step of the process has been meticulously detailed and photographed.

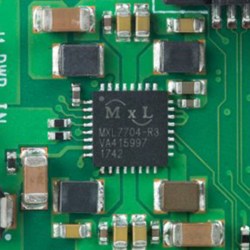

The construction methods utilized in this project run the gamut from basic woodworking tools for the outside wooden frame, to a laser cutter to create the graphical overlay on the device’s clear acrylic face. [Michael] even went as far as having a custom PCB made to connect up all the LEDs, switches, and buttons to the Arduino Nano by way of an MCP23017 I2C I/O expander.

Even if you aren’t looking to build an elaborate child’s toy that would make some adults jealous, there’s a wealth of first-hand information about turning an idea into a final physical device. It isn’t always easy, and things don’t necessarily go as planned, but as [Michael] clearly demonstrates: the final product is absolutely worth putting the effort in.

Seeing how many hackers are building mock spacecraft control panels for their children, we can’t help but wonder if any of them will adopt us.

Continue reading “A Hacker’s Epic Quest To Keep His Son Entertained”

Instead of a sliding wall panel, [HighwingZ] has built a hexagonal container. Five of the six sides contain bottles to fill the drink with, the last panel contains the spigot and a spot for the glass. The machine works by weighing the liquid that gets poured into the glass using a load cell connected to a HX711 load cell amplifier. An aquarium pump is used to push air into whichever bottle has been selected via some magnetic valves which forces the liquid up its tube and into the glass. A simple touch screen UI is used so the user can select which drink and how much of it gets poured. All of this is connected to a Raspberry Pi to control it all.

Instead of a sliding wall panel, [HighwingZ] has built a hexagonal container. Five of the six sides contain bottles to fill the drink with, the last panel contains the spigot and a spot for the glass. The machine works by weighing the liquid that gets poured into the glass using a load cell connected to a HX711 load cell amplifier. An aquarium pump is used to push air into whichever bottle has been selected via some magnetic valves which forces the liquid up its tube and into the glass. A simple touch screen UI is used so the user can select which drink and how much of it gets poured. All of this is connected to a Raspberry Pi to control it all.