It might seem impossible, but what you’re looking at is a Sony PlayStation game being played on a Nintendo Game Boy Advance. The resolution is miserable and the GBA doesn’t have nearly enough buttons to do most 3D games justice, but it’s working. There’s even audio support, although turning it on will slow things down considerably.

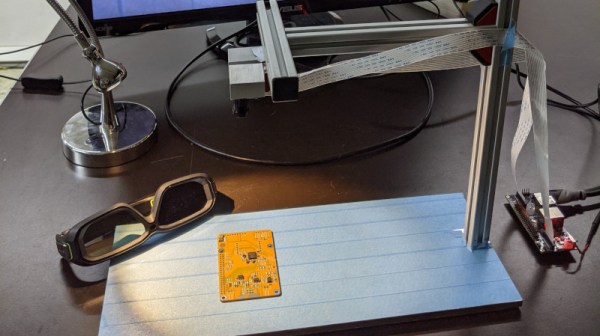

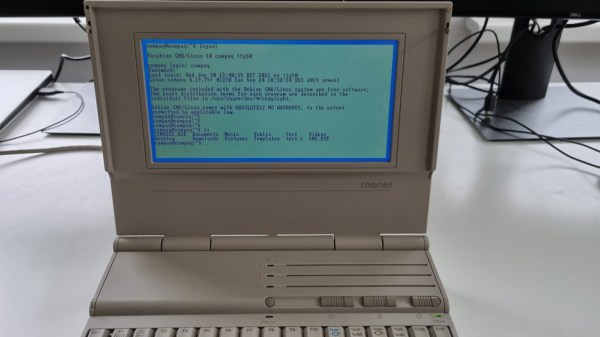

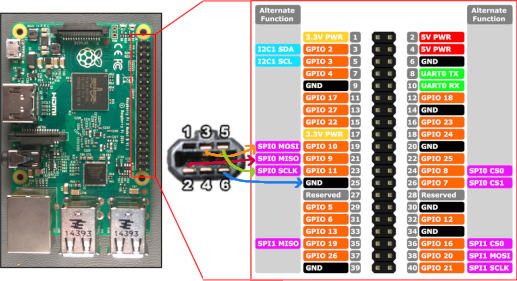

How does it work? The trick is that creator [Rodrigo Alfonso] is actually emulating the PlayStation on a Raspberry Pi and simply using Nintendo’s handheld as an external display and controller. We say “simply”, but of course, it’s anything but. The GitHub page for the project goes into impressive detail on how the whole thing works, but the short version is that the video data is sent from the Linux framebuffer to a small program running on the GBA over the handheld’s serial port using SPI. In testing he was able to push 2.56 Mbps through the link, which is a decent amount of bandwidth when you’ve only got to keep a 240 × 160 screen filled.

Perhaps the best part is that you don’t even need a flash cart to try it at home. [Rodrigo] is using a trick we’ve seen in other GBA projects, where the program is actually transferred to the handheld over the link cable at boot time.

Perhaps the best part is that you don’t even need a flash cart to try it at home. [Rodrigo] is using a trick we’ve seen in other GBA projects, where the program is actually transferred to the handheld over the link cable at boot time.

Nintendo introduced this “multiboot” feature so multiplayer games could be played between systems even if they didn’t all have a physical cartridge, but now that hackers have cracked the code, it means you can run arbitrary code on a completely unmodified console; though it does get wiped as soon as you power it off.

[Rodrigo] provides all the information and software you need to try it at home, you just need a Raspberry Pi, a Game Boy Advance, and Link Cable you don’t mind cutting up; far less hardware than is required by the similar project to run DOOM on the NES. Since he’s tied everything into the popular RetroPie frontend, we imagine it would even work when emulating earlier 2D consoles; which would be a much better fit for the GBA’s display and limited inputs.