To have a proper gaming “rig”, you need more than a powerful GPU and heaps of RAM. You’ve also got to install a clear side-panel so lesser mortals can ogle your wiring, and plenty of multicolored LEDs to make sure it’s never actually dark when you’re up playing at 2 AM. Or at least, that’s what the Internet has led us to believe.

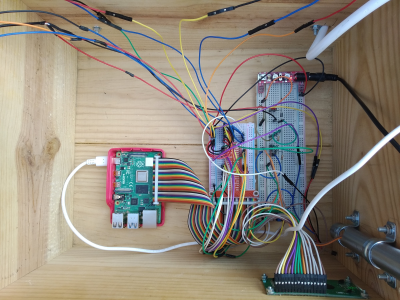

The latest project from [Michael Pick] certainly isn’t doing anything to dispel that stereotype. In fact, it’s absolutely reveling in it. The goal was to recreate the look of a high-end custom gaming PC on a much smaller scale, with a Raspberry Pi standing in for the “motherboard”. Assuming you’re OK with streaming them from a more powerful machine on the network, this diminutive system is even capable of playing modern titles.

But really, the case is the star of the show here. Starting with a 3D printed frame, [Michael] really went all in on the details. We especially liked the little touches such as the fiber optics used to bring the Pi’s status and power LEDs out to the top of the case, and the tiny and totally unnecessary power button. There’s even a fake graphics card inside, with its own functional fan.

But really, the case is the star of the show here. Starting with a 3D printed frame, [Michael] really went all in on the details. We especially liked the little touches such as the fiber optics used to bring the Pi’s status and power LEDs out to the top of the case, and the tiny and totally unnecessary power button. There’s even a fake graphics card inside, with its own functional fan.

Even if you’re not interested in constructing custom enclosures for your Raspberry Pi, there are plenty of tips and tricks in the video after the break that are more than worthy of filing away for future use. For example, [Michael] shows how he fixed the fairly significant warping on his 3D printed case with a liberal application of Bondo and a straight-edge to compare it to.

This isn’t the first time we’ve seen a Raspberry Pi masquerade as a high-end computer, but it’s surely the most effort we’ve ever seen put into the gag.

Continue reading “Mini “Gaming PC” Nails The Look, Streams The Games”