Modern motherboards don’t come with ISA slots, and almost everybody is fine with that. If you really want one, though, there are ways to get one. [TheRasteri] explains how in a forum post on the topic.

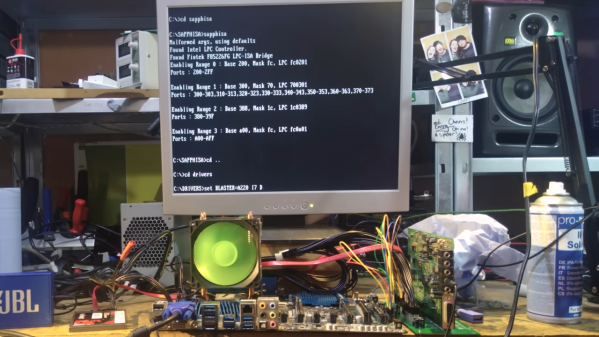

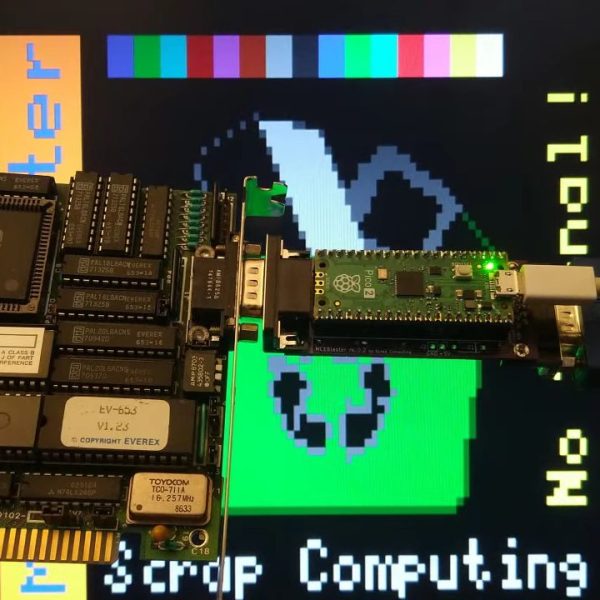

Believe it or not, some post-2010 PC hardware can still do ISA, it’s just that the slots aren’t broken out or populated on consumer hardware. However, if you know where to look, you can hack in an ISA hookup to get your old hardware going. [TheRasteri] achieves this on motherboards that have the LPC bus accessible, with the use of a custom PCB featuring the Fintek F85226 LPC-to-ISA bridge. This allows installing old ISA cards into a much more modern PC, with [TheRasteri] noting that DMA is fully functional with this setup—important for some applications. Testing thus far has involved a Socket 755 motherboard and a Socket 1155 motherboard, and [TheRasteri] believes this technique could work on newer hardware too as long as legacy BIOS or CSM is available.

It’s edge case stuff, as few of us are trying to run Hercules graphics cards on Windows 11 machines or anything like that. But if you’re a legacy hardware nut, and you want to see what can be done, you might like to check out [TheRasteri’s] work over on Github. Video after the break.