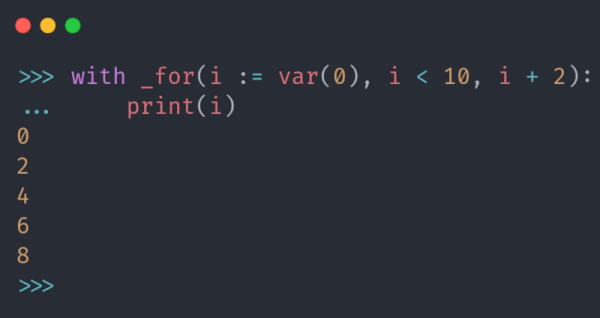

[Ihsan Kehribar] points out a clever trick you can use to quickly and efficiently compute the logarithm of a 32-bit integer. The technique relies on the CLZ instruction which counts the number of leading zeros in a machine word and is available in many modern processors. Typical algorithms used to compute logarithms are not quick and have a variable execution time depending on the input value. The technique [Ihsan] is using is both fast and has a constant run time.

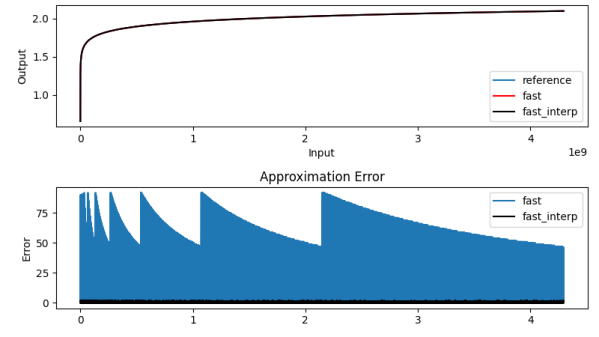

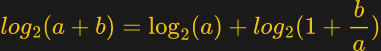

The above equation summarized the math behind the algorithm. We get the first term easily using the CLZ instruction. Using the remainder and a pre-computed lookup table, it is possible to get the second term to various degrees of accuracy, depending on how big you make the table and whether or not you take the performance hit of interpolation or not — those of a certain age will no likely groan at the memory of doing interpolation by hand from logarithm tables in high school math class. [Ihsan] has posted an MIT-licensed implementation of this technique in his GitHub repository, which includes both the C-language algorithm and Python tools to generate the lookup table and evaluate the errors.

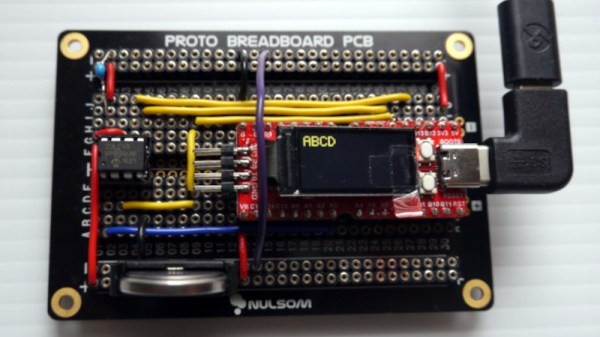

Why would you do this? Our first thought was real-time streaming DSP operations, where you want fast and deterministic calculations, and [Ihsan]’s specifically calls out embedded audio processing as one class of such applications. And he should know, after all, since he developed a MIDI capable polyphonic FM synthesizer on a Cortex M0 that we covered way back in 2015.