Deep Neural Networks can be pretty good at identifying images — almost as good as they are at attracting Silicon Valley venture capital. But they can also be fairly brittle, and a slew of research projects over the last few years have been working on making the networks’ image classification less likely to be deliberately fooled.

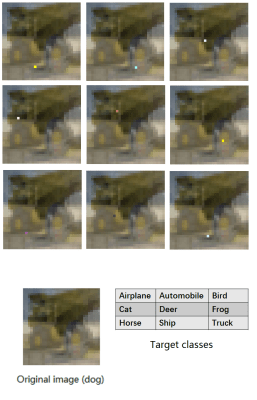

One particular line of attack involves adding particularly-crafted noise to an image that flips some bits in the deep dark heart of the network, and makes it see something else where no human would notice the difference. We got tipped with a YouTube video of a one-pixel attack, embedded below, where changing a single pixel in the image would fool the network. Take that robot overlords!

Or not so fast. Reading the fine-print in the cited paper paints a significantly less gloomy picture for Deep Neural Nets. First, the images in question were 32 pixels by 32 pixels to begin with, so each pixel matters, especially after it’s run through a convolution step with a few-pixel window. The networks they attacked weren’t the sharpest tools in the shed either, with somewhere around a 68% classification success rate. What this means is that the network was unsure to begin with for many of the test images — making it flip from its marginally best (correct) first choice to a second choice shouldn’t be all that hard.

This isn’t to say that this line of research, adversarial training of the networks, is bogus. The idea that making neural nets robust to small changes is important. You don’t want turtles to be misclassified as guns, for instance, or Hackaday’s own Steven Dufresne misclassified as a tobacconist. And you certainly don’t want speech recognition software to be fooled by carefully crafted background noise. But if a claim of “astonishing results” on YouTube seems too good to be true, well, maybe it is.

Thanks [kamathin] for the tip!