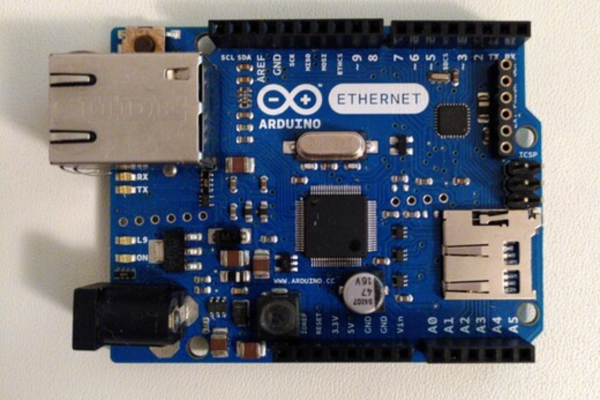

Most computer operating systems suffer from some version of “DLL hell” — a decidedly Windows term, but the concept applies across the board. Consider doing embedded development which usually takes a few specialized tools. You write your embedded system code, ship it off, and forget about it for a few years. Then, the end-user wants a change. Too bad the compiler you used requires some library that has changed so it no longer works. Oh, and the device programmer needs an older version of the USB library. The Python build tools use Python 2 but your system has moved on. If the tools you need aren’t on the computer anymore, you may have trouble finding the install media and getting it to work. Worse still if you don’t even have the right kind of computer for it anymore.

One way to address this is to encapsulate all of your development projects in a virtual machine. Then you can save the virtual machine and it includes an operating system, all the right libraries, and basically is a snapshot of how the project was that you can reconstitute at any time and on nearly any computer.

In theory, that’s great, but it is a lot of work and a lot of storage. You need to install an operating system and all the tools. Sure, you can get an appliance image, but if you work on many projects, you will have a bunch of copies of the very same thing cluttering things up. You’ll also need to keep all those copies up-to-date if you need to update things which — granted — is sort of what you are probably trying to avoid, but sometimes you must.

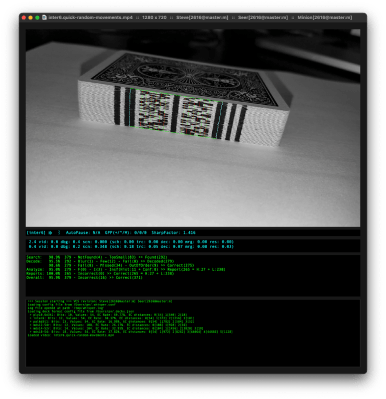

Docker is a bit lighter weight than a virtual machine. You still run your system’s normal kernel, but essentially you can have a virtual environment running in an instant on top of that kernel. What’s more, Docker only stores the differences between things. So if you have ten copies of an operating system, you’ll only store it once plus small differences for each instance.

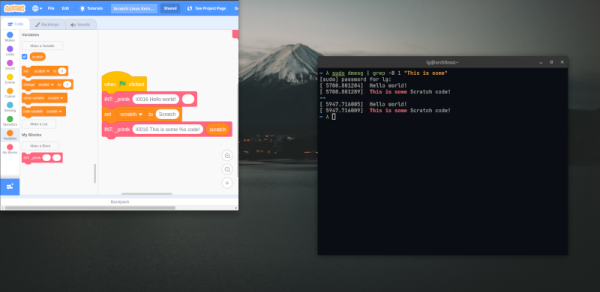

The downside is that it is a bit tough to configure. You need to map storage and set up networking, among other things. I recently ran into a project called Dock that tries to make the common cases easier so you can quickly just spin up a docker instance to do some work without any real configuration. I made a few minor changes to it and forked the project, but, for now, the origin has synced up with my fork so you can stick with the original link.

Continue reading “Linux Fu: Docking Made Easy” →