In a world with finite storage and an infinite need for more storage space, data compression becomes a very necessary problem. Several algorithms for data compression may be more familiar – Huffman coding, LZW compression – and some a bit more arcane.

[Labunsky] decided to put to use his knowledge of steganography to create a wholly unique form of file compression, perhaps one that may gain greater notoriety among other information theorists.

Steganography refers to the method of concealing messages or files within another file, coming from the Greek words steganos for “covered or concealed” and graphe for “writing”. The practice has been around for ages, from writing in invisible ink to storing messages in moon cakes. The methods used range from hiding messages in images to evade censorship to hiding viruses in files to cause mayhem.

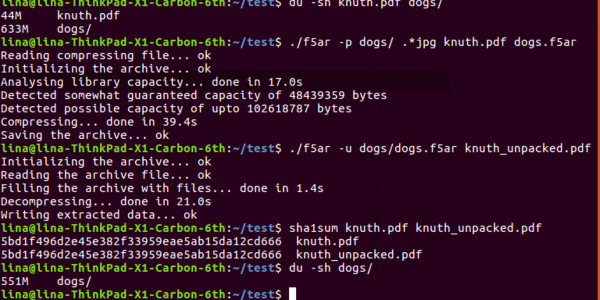

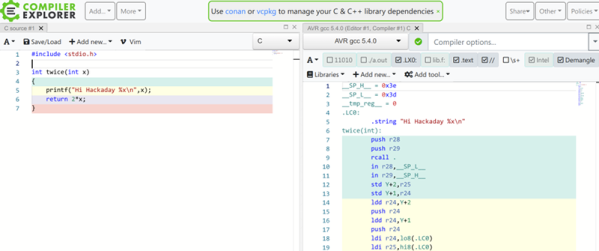

The compression technique they ended up implementing is based on the F5 algorithm that embeds binary data into JPEG files to reduce total space in the memory. The compression uses libjpeg for JPEG decoding and encoding, pcre for POSIX regular expressions support, and tinydir for platform-independent filesystem traversal. One of the major modifications was to save computation resources by disabling a password-based permutative straddling that uniformly spreads data among multiple files.

One caveat – changing even one bit of the compressed file could lead to total corruption of all of the data stored, so use with caution!