When it comes to an engineering marvel like the James Webb Space Telescope, the technology involved is so specialized that there’s precious little the average person can truly relate to. We’re talking about an infrared observatory that cost $10 billion to build and operates at a temperature of 50 K (−223 °C; −370 °F), 1.5 million kilometers (930,000 mi) from Earth — you wouldn’t exactly expect it to share any parts with your run-of-the-mill laptop.

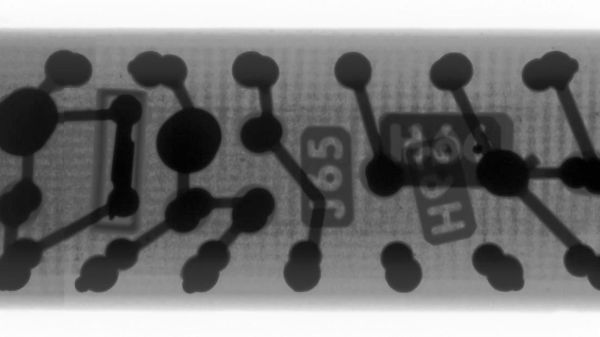

But it would be a lot easier for the public to understand if it did. So it’s really no surprise that this week we saw several tech sites running headlines about the “tiny solid state drive” inside the James Webb Space Telescope. They marveled at the observatory’s ability to deliver such incredible images with only 68 gigabytes of onboard storage, a figure below what you’d expect to see on a mid-tier smartphone these days. Focusing on the solid state drive (SSD) and its relatively meager capacity gave these articles a touchstone that was easy to grasp by a mainstream audience. Even if it was a flawed comparison, readers came away with a fun fact for the water cooler — “My computer’s got a bigger drive than the James Webb.”

Of course, we know that NASA didn’t hit up eBay for an outdated Samsung EVO SSD to slap into their next-generation space observatory. The reality is that the solid state drive, known officially as the Solid State Recorder (SSR), was custom built to meet the exact requirements of the JWST’s mission; just like every other component on the spacecraft. Likewise, its somewhat unusual 68 GB capacity isn’t just some arbitrary number, it was precisely calculated given the needs of the scientific instruments onboard.

With so much buzz about the James Webb Space Telescope’s storage capacity, or lack thereof, in the news, it seemed like an excellent time to dive a bit deeper into this particular subsystem of the observatory. How is the SSR utilized, how did engineers land on that specific capacity, and how does its design compare to previous space telescopes such as the Hubble?

Continue reading “How Does The James Webb Telescope Phone Home?”