If you enjoy old military hardware, you probably know that Harris made quite a few heavy-duty pieces of radio gear. [K6YIC] picked up a nice example: the Harris RF-130 URT-23. These were frequently used in the Navy and some other service branches to communicate in a variety of modes on HF. The entire set included an exciter, an amplifier, an antenna tuner, and a power supply and, in its usual configuration, can output up to a kilowatt. The transmitter needs some work, and he’s done three videos on the transmitter already. He’s planning on several more, but there’s already a lot to see if you enjoy this older gear. You can see the first three below and you’ll probably want to watch them all, but if you want to jump right to the tear down, you can start with the second video.

You can find the Navy manual for the unit online, dated back to 1975. It’s hard to imagine how much things have changed in 50 years. These radios use light bulbs and weigh almost 500 pounds. [Daniel] had to get his shop wired for 220 V just to run the beast.

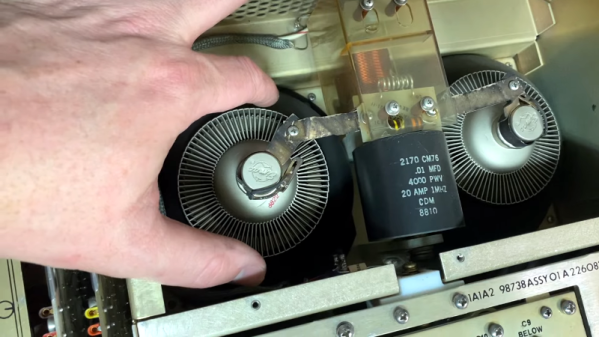

It is amusing that some of this old tube equipment had a counter to tell you how many hours the tubes inside had been operating so you could replace them before they were expected to fail. To keep things cool, there’s a very noisy 11,000 RPM fan. The two ceramic final amplifier tubes weigh over 1.5 pounds each!

The third video shows the initial power up. Like computers, if you remember when equipment was like this, today’s lightweight machines seem like toys. Of course, everything works better these days, so we won’t complain. But there’s something about having a big substantial piece of gear with all the requisite knobs, switches, meters, and everything else.

We can’t wait to see the rest of the restoration and to hear this noble radio on the air again. You can tell that [Daniel] loves this kind of gear and you can pick up a lot of tips and lingo watching the videos.

Continue reading “Reactivating A Harris RF-130 URT-23 Transmitter”