The Garden of Eden Creation Kit, or GECK, is the MacGuffan of Fallout 3 and the name of the modding tool for the same game. In the game, the GECK is a terraforming tool designed to turn the wasteland of Washington DC into its more natural form — an inhospitable swamp teeming with mosquitos.

A device to automatically terraform any environment is improbable now as it was in Wrath of Khan, but a “Garden of Eden Kit” is still a really great name. For their Hackaday Prize entry, [atheros] is building a simplified version of this terraforming device. Instead of turning the Tidal Basin into potable water or turning a nebula into a verdant planet, [atheros]’s Garden of Eden Watering Kit turns empty potted plants into a lush harvest of herbs.

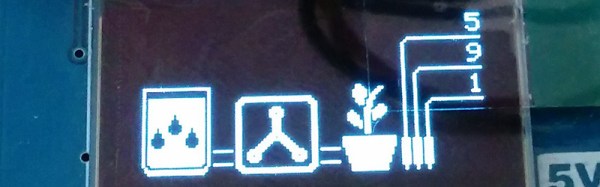

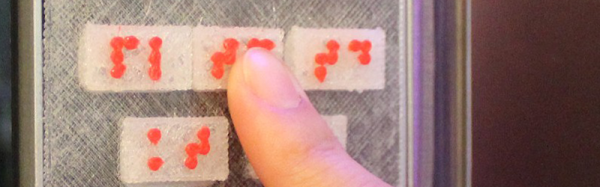

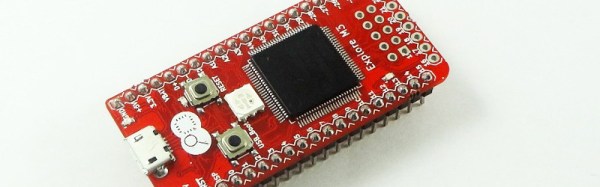

The device, like most home gardening solutions presented in this year’s Hackaday Prize, isn’t geared towards irrigating acres of crops. This is just a simple, small device meant to water a few herbs growing in a pot on a balcony. The hardware consists of a Teensy LC and a small OLED for command and control. A soil moisture sensor goes into each pot, and a few 12V peristaltic pumps water the plants from a bucket reservoir.

For the home gardener, it’s the perfect setup to grow some herbs, some chilis, or a cherry tomato plant that produces a year’s worth of tomatoes every week. It’s a great adaptation of off the shelf tech, and a great entry for the Hackaday Prize.