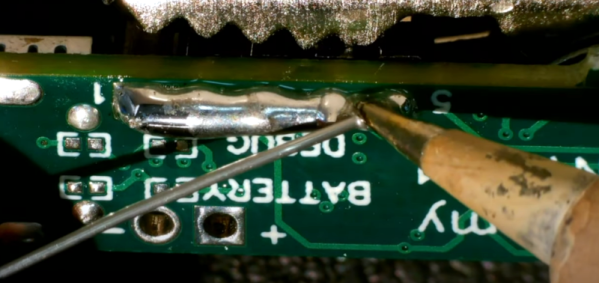

As our own Elliot Williams laid out, many people think that soldering is a key skill for electronics, but we don’t as often think about desoldering. Even if you are perfect in your technique, there’s always the chance you’ll put in a bad part or have a part fail later and it will need replacement. [Robert] has a short video showing his method for removing through-hole components and you can see it below.

This isn’t the first time we’ve seen it, of course. In fact, it is very much like using hot air, although it doesn’t require hot air, just extra solder and a regular iron. Of course, if we knew that connector was bad, we’d have been tempted to cut each pin apart and remove them one at a time. Heating a joint and then slamming your hand on the bench can work wonders.

We always think desoldering pumps are a good idea, but the electric ones tend to be anemic. The ones with the springs are usually better, but still have limitations. In the end, we’ll stick with using hot air, but if all you have is an iron, this method is worth checking out. You might also be interested in the needle method.