Humanity is better when we work together. Nowhere is this more true than when it comes to Citizen Scientists — the concept that scientific advancement isn’t reserved to the trained professionals, but benefits when a larger population of thinkers collaborates with the community of trained researchers. This is the goal of the Citizen Scientist challenge round for the Hackaday Prize. Let’s build something that enables citizens to be scientists.

We’ll divide $20,000 evenly between twenty projects that target Citizen Scientists. Enter now and build your prototype by July 11th for your chance to win. Even better, if you are selected as one of those 20 finalists you’ll compete for the top prizes, $150k and a residency at the Supplyframe Design Lab in Pasadena. Second through fifth place finishers will get $25k, $10k, $10k, and $5k.

You love design challenges and this one has powerful potential. We’ve seen builds like this in the finals during previous years of the Hackaday Prize. In 2014, RamanPi was recognized as the 5th place winner. The project seeks to reduce the expense of acquiring a Raman Spectrometer which is used for analyzing chemical substances. The design used parametric models for the optic jigs used by the machine. The idea is that a university could buy their own optics, adjust the models for the properties of those lenses and mirrors, then 3D print the parts to build the apparatus.

You love design challenges and this one has powerful potential. We’ve seen builds like this in the finals during previous years of the Hackaday Prize. In 2014, RamanPi was recognized as the 5th place winner. The project seeks to reduce the expense of acquiring a Raman Spectrometer which is used for analyzing chemical substances. The design used parametric models for the optic jigs used by the machine. The idea is that a university could buy their own optics, adjust the models for the properties of those lenses and mirrors, then 3D print the parts to build the apparatus.

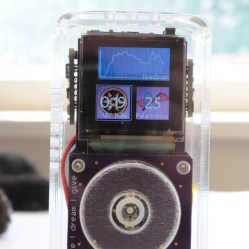

Also a winner in 2014, the Open Science Tricorder was recognized as the fourth place finisher. Based on the form factor and functionality of the iconic Star Trek technology, the Open Science Tricorder combines three or more sensor technologies with a user interface. It provides a hands-on experience for students learning about the properties of the world around them, and a handheld sensor suite to anyone interested in undertaking their own research projects.

Also a winner in 2014, the Open Science Tricorder was recognized as the fourth place finisher. Based on the form factor and functionality of the iconic Star Trek technology, the Open Science Tricorder combines three or more sensor technologies with a user interface. It provides a hands-on experience for students learning about the properties of the world around them, and a handheld sensor suite to anyone interested in undertaking their own research projects.

The Citizen Scientist challenge round begins right now. Get started on your build today and show us what you can do to solve a technology problem with your prototyping skills. Good luck!