Fully understanding the planet’s complex ecosystem takes data, and lots of it. Unfortunately, the ability to collect detailed environmental data on a large scale with any sort of accuracy has traditionally been something that only the government or well-funded institutions have been capable of. Building and deploying the sensors necessary to cover large areas or remote locations simply wasn’t something the individual could realistically do.

But by leveraging modular hardware and open source software, the FieldKit from [Conservify] hopes to even the scales a bit. With an array of standardized sensors and easy to use software tools for collating and visualizing collected data, the project aims to empower independent environmental monitoring systems that can scale from a handful of nodes up to several hundred.

We’ve all seen more than enough DIY environmental monitoring projects to know there’s nothing particularly new or exciting about stuffing a few cheap sensors into a plastic container. But putting high quality, reliable hardware into large scale production is another thing entirely. Especially when your target user may have limited technical knowledge.

We’ve all seen more than enough DIY environmental monitoring projects to know there’s nothing particularly new or exciting about stuffing a few cheap sensors into a plastic container. But putting high quality, reliable hardware into large scale production is another thing entirely. Especially when your target user may have limited technical knowledge.

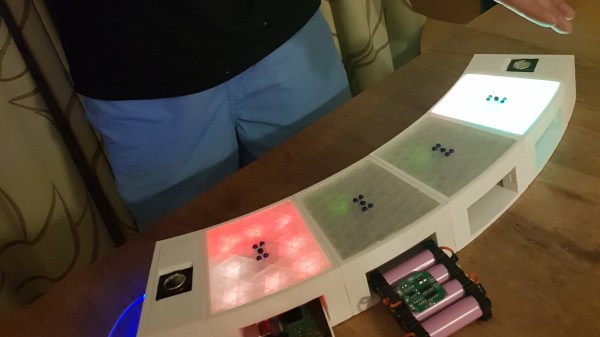

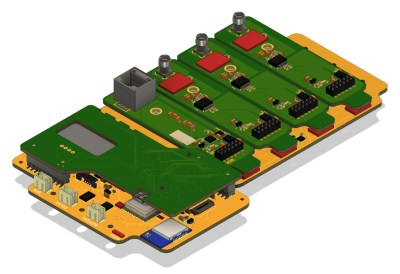

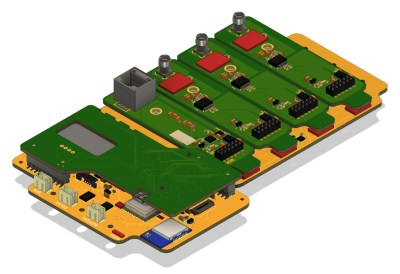

That’s why FieldKit is designed around a common backplane with modular sensors and add-on boards that can be plugged in and easily configured with a smartphone application. Whether the node is going to be mounted to a pole and powered by a solar panel, or attached to a buoy, most of the hardware stays the same.

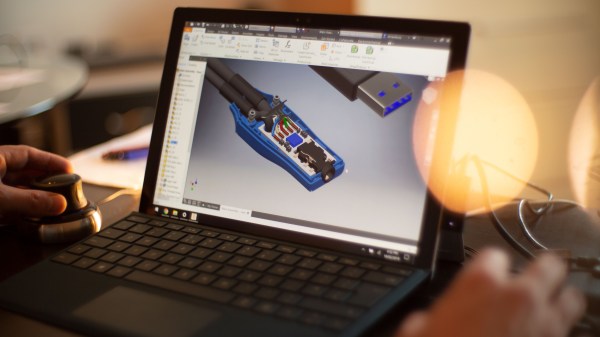

While the electronics and the software interface are naturally the stars of the show here, we can’t help but also be impressed with the enclosure for the FieldKit. It seems a minor thing, but as we’ve seen from the projects that have come our way over the years, finding a box to put your hardware in that’s affordable, adaptable, and weatherproof is often a considerable challenge in itself. Rather than using something commercially available, [Conservify] has designed their own enclosure that’s inspired by the heavy duty (but prohibitively expensive) cases from Pelican. It features a replaceable panel on one side where the user can pop whatever holes will be necessary to wire up their particular project without compromising the case itself; just get a new panel when you want to reconfigure the FieldKit for some other task. Prototypes have already been 3D printed, and the team will be moving to injection molded versions in the near future.

As a finalist in the 2019 Hackaday Prize, FieldKit exemplifies everything we’re looking for this year: a clear forward progression from prototype to final hardware, an obvious need for mass production, and the documentation necessary to show why this project is deserving of the $125,000 grand prize up for grabs.

Continue reading “An Open Source Toolbox For Studying The Earth” →