There’s an old saying in the amateur radio community that when it comes to antennas all you need is a piece of wet string. This may be a little fanciful, but it’s certainly true that an effective antenna can be made with surprisingly little in the way of conductor. It’s something [Evan Pratten VZ3ZZA] demonstrates amply with a description of the antenna he took camping in a Canadian provincial park.

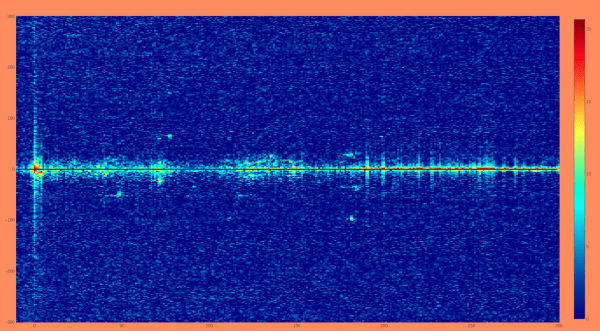

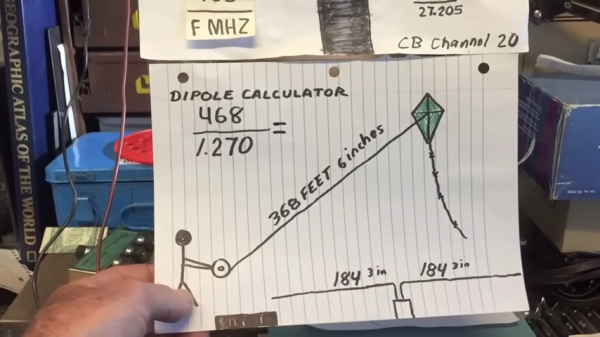

Most of us would try some form of dipole on our adventures, but the antenna he’s using caught our eye as it’s described as an end-fed half-wave, but it has both a half-wave and quarter-wave element. Made from speaker cable or in this case thin mains cable for lamps, it’s obviously far from a perfect match and requires an ATU, but it generates an impressive array of FT4 contacts on a pretty meagre power level. We particularly like his in-plain-sight test run in the parking lot of a supermarket.

We frequently talk about the diversity of pursuits in amateur radio aside from that of the chequebook ham, and this project shows one of those. The world of QRP, operating at extreme low power, is not expensive to enter and can be extremely rewarding.