If you live in a city, you’re constantly swimming in a thick soup of radio-frequency energy. FM radio stations put out hundreds of kilowatts each into the air. Students at the University of Washington, [Anran Wang] and [Vikram Iyer], asked themselves if they could harness this background radiation to transmit their own FM radio station, if only locally. The answer was an amazing yes.

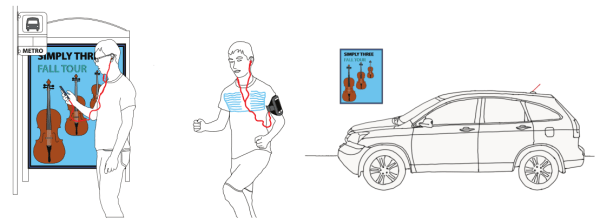

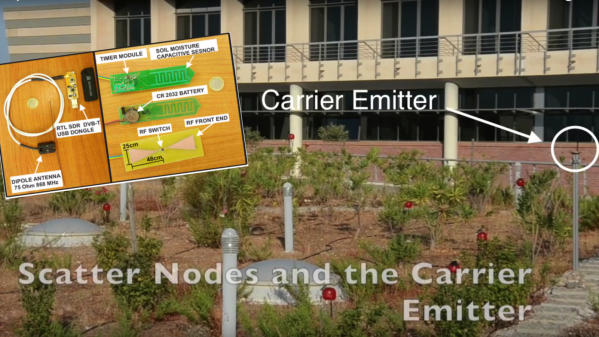

The trailer video, embedded below, demos a couple of potential applications, but the paper (PDF) has more detail for the interested. Basically, they turn on and off an absorbing antenna at a frequency that’s picked so that it modulates a strong FM signal up to another adjacent channel. Frequency-modulating this backscatter carrier frequency adds audio (or data) to the product station.

One of the cooler tricks that they pull off with this system is to inject a second (stereo) channel into a mono FM station. Since FM radio is broadcast as a mono signal, with a left-minus-right signal sent alongside, they can make a two-channel stereo station by recreating the stereo pilot carrier and then adding in their own difference channel. Pretty slick. Of course, they could send data using this technique as well.

Why do this? A small radio station using backscatter doesn’t have to spend its power budget on the carrier. Instead, the device can operate on microwatts. Granted, it’s only for a few feet in any given direction, but the station broadcasts to existing FM radios, rather than requiring the purchase of an RFID reader or similar device. It’s a great hack that piggybacks on existing infrastructure in two ways. If this seems vaguely familiar, here’s a similar idea out of the very same lab that’s pulling off essentially the same trick indoors with WiFi signals.

So who’s up for local reflected pirate radio stations?

Continue reading “Backscatter Your Own FM Pirate Radio Station”