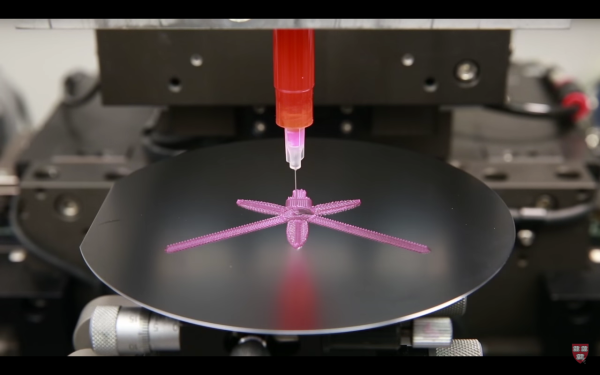

What do you print with your 3D printer? Key chains? More printer parts (our favorite)? Enclosures for PC boards? At Johns Hopkins, they want to print bones. Not Halloween skeletons, either. Actual bones for use in bodies.

According to Johns Hopkins, over 200,000 people a year need head or face bone replacements due to birth defects, trauma, or surgery. Traditionally, surgeons cut part of your leg bone that doesn’t bear much weight out and shape it to meet the patient’s need. However, this has a few problems. The cut in the leg isn’t pleasant. In addition, it is difficult to create subtle curved shapes for a face out of a relatively straight leg bone.

This is an obvious application for 3D printing if you could find a suitable material to produce faux bones. The FDA allows polycaprolactate (PCL) plastic for other clinical uses and it is attractive because it has a relatively low melting point. That’s important because mixing in biological additives is difficult to do at high temperatures.

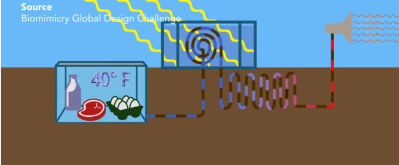

The aim of this challenge is to transform the global food system using sustainable approaches that emulate natural process. Entries must address a problem somewhere in the food supply chain, a term that could apply to anything from soil modification to crop optimization to harvest and storage technologies. Indeed, the 2015 winner in the Student category was for a

The aim of this challenge is to transform the global food system using sustainable approaches that emulate natural process. Entries must address a problem somewhere in the food supply chain, a term that could apply to anything from soil modification to crop optimization to harvest and storage technologies. Indeed, the 2015 winner in the Student category was for a