Any modern computer with an x86 processor, whether it’s Intel or AMD, is a lost cause for software freedom and privacy. We harp on this a lot, but it’s worth repeating that it’s nearly impossible to get free, open-source firmware to run on them thanks to the Intel Management Engine (IME) and the AMD Platform Security Processor (PSP). Without libre firmware there’s no way to trust anything else, even if your operating system is completely open-source.

The IME or PSP have access to memory, storage, and the network stack even if the computer is shut down, and even after the computer boots they run at such a low level that the operating system can’t be aware of what they’re really doing. Luckily, there’s a dark horse in the race in the personal computing world that gives us some hope that one day there will be an x86 competitor that allows their users to have a free firmware that they can trust. ARM processors, which have been steadily increasing their user share for years but are seeing a surge of interest since the recent announcement by Apple, are poised to take over the personal computing world and hopefully allow us some relevant, modern options for those concerned with freedom and privacy. But in the real world of ARM processors the road ahead will decidedly long, windy, and forked.

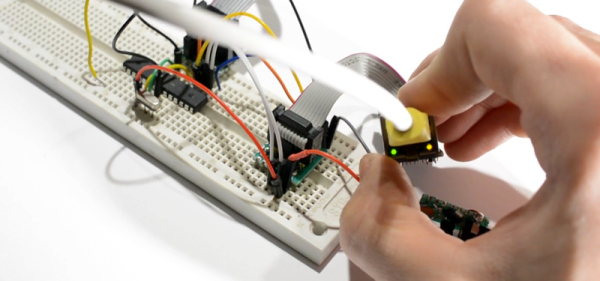

Even ignoring tedious nitpicks that the distinction between RISC vs CISC is more blurred now than it was “back in the day”, RISC machines like ARM have a natural leg up on the x86 CISC machines built by Intel and AMD. These RISC machines use fewer instructions and perform with much more thermal efficiency than their x86 competitors. They can often be passively cooled, avoiding need to be actively cooled, unlike many AMD/Intel machines that often have noisy or bulky fans. But for me, the most interesting advantage is the ability to run ARM machines without the proprietary firmware present with x86 chips.

Continue reading “Degrees Of Freedom: Booting ARM Processors”