Despite the best efforts of the RepRap community over the last twenty years, self-replicating 3D printers have remained a stubbornly elusive goal, largely due to the difficulty of printing electronics. [Brian Minnick]’s fully-printed 3D printer could eventually change that, and he’s already solved an impressive number of technical challenges in the process.

[Brian]’s first step was to make a 3D-printable motor. Instead of the more conventional stepper motors, he designed a fully 3D-printed 3-pole brushed motor. The motor coils are made from solder paste, which the printer applies using a custom syringe-based extruder. The paste is then sintered at a moderate temperature, resulting in traces with a resistivity as low as 0.001 Ω mm, low enough to make effective magnetic coils.

brushed motor10 Articles

3D Print Yourself These Mini Workshop Tools

Kitting out a full workshop can be expensive, but if you’re only working on small things, it can also be overkill. Indeed, if your machining tends towards the miniature, consider building yourself a series of tiny machines like [KendinYap] did. In the video below, you can see the miniature electric sander, table saw, drill press, and cut-off saw put through their paces.

Just because the machines are small, doesn’t mean they’re not useful. In fact, they’re kind of great for doing smaller jobs without destroying what you’re working on. The tiny belt sander in particular appeals in this case, but the same applies to the drill press as well. [KendinYap] also shows off a tiny table and circular saw. The machines are straightforward in their design, relying largely on 3D printed components. They’re all powered by basic DC brushed motors which are enough to get the job done on the small scale.

They look particularly good if tiny scale model-making is your passion.

Continue reading “3D Print Yourself These Mini Workshop Tools”

Brushless ESC Becomes Dual-Motor Brushed ESC With A Few Changes

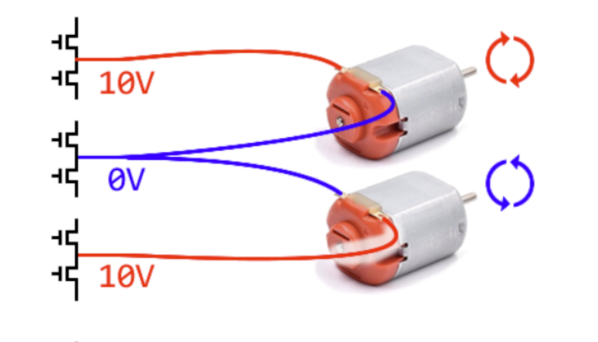

What is a brushless ESC, really? Well, generally, it’s usually a microcontroller with a whole lot of power transistors hanging off it to drive three phases of brushless motor coils. [Frank Zhao] realised that with a little reprogramming, you could simply use a brushless ESC to independently run two brushed motors. Thus, he whipped up a custom firmware for various AM32-compatible ESCs to do just that.

The idea of the project is to enable a single lightweight ESC to run two brushed motors for combat robots. Dual-motor brushed ESCs can be hard to find and expensive, whereas single-motor brushless ESCs are readily available. The trick is to wire up the two brushed motors such that each motor gets one phase wire of its own, and the two motors share the middle phase wire. This allows independent control of both motors via the brushless ESC’s three half-bridges, by setting the middle wire to half voltage. Depending on how you set it up, the system can be configured in a variety of ways to suit different situations.

[Frank’s] firmware is available on Github for the curious. He lists compatible ESCs there, and notes that you’ll need to install the AM32 ESC firmware before flashing his version to make everything work correctly.

The VESC project has long supported brushed motor operation, too, though not in a tandem configuration. Meanwhile, if you’ve got your own neat ESC hacks, don’t hesitate to hit us up on the tipsline!

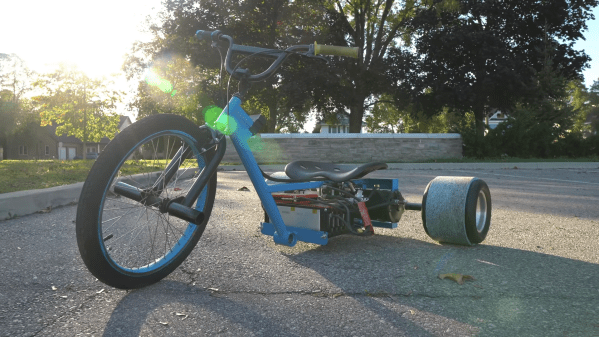

Heavy-Duty Starter Motor Powers An Awesome Drift Trike

Starter motors aren’t typically a great choice for motorized projects, as they’re designed to give engines a big strong kick for a few seconds. Driving them continuously can often quickly overheat them and burn them out. However, [Austin Blake] demonstrates that by choosing parts carefully, you can indeed have some fun with a starter motor-powered ride.

[Austin] decided to equip his drift trike with a 42MT-equivalent starter motor typically used in heavy construction machinery. The motor was first stripped of its solenoid mechanism, which is used to disengage the starter from an engine after it has started. The housing was then machined down to make the motor smaller, and a mount designed to hold the starter on the drift trike’s frame.

A 36V battery pack was whipped up using some cells [Austin] had lying around, and fitted with a BMS for safe charging. The 12V starter can draw up to 1650 amps when cranking an engine, though the battery pack can only safely deliver 120 amps continuously. A Kelly controller for brushed DC motors was used, set up with a current limit to protect the battery from excessive current draw.

The hefty motor weighs around 50 pounds, and is by no way the lightest or most efficient drive solution out there. However, [Austin] reports that it has held up just fine in 20 minutes of near-continuous testing, despite being overvolted well beyond its design specification. The fact it’s operating at a tenth of its rated current may also have something to do with its longevity. It also bears noting that many YouTube EVs die shortly after they’re posted. Your mileage may vary.

For a more modern solution, you might consider converting an alternator into a brushless electric motor. Video after the break.

Continue reading “Heavy-Duty Starter Motor Powers An Awesome Drift Trike”

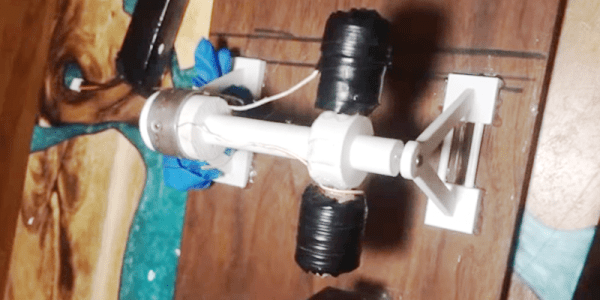

Low Buck PVC ROV IS Definitely A MVP

Do you have a hundred bucks and some time to kill? [Peter Sripol] invites you to come along with him and build a remotely operated submarine with only the most basic, easily accessible parts, as you can see in the video below the break.

Using nothing more than PVC pipe, an Ethernet cable, and a very basic electrical system, [Peter] has built a real MVP of a submarine. No, not Most Valuable Player; Minimum Viable Product. You see, there’s not a microcontroller, motor controller, sensor, or MOSFET to be found except for that which might reside inside the knock-off GoPro style camera which is encased in a candle wax sealed enclosure.

Instead, simple brushed motors live right out in the open water. Single pole double throw switches are connected to 100 feet of Ethernet cable and control the relays powering the motors. The camera signal is brought back to the controller through the same cable. Simple is the key to the build, and we have to admit that for all of its Minimum Viability, the little ROV has a lot going for it. [Peter] even manages to use the little craft to find and make possible the retrieval of a crustacean encrusted shopping cart from a saltwater canal. Not bad, little rover, not bad.

Also noteworthy is that the video below has its own PVC ROV Sea Shanty, which is something you just don’t hear every day.

Underwater ROV builds are the sort of thing almost every hacker thinks about doing at least once, and some hackers even include Lego, magnets, and balloons in their builds! Continue reading “Low Buck PVC ROV IS Definitely A MVP”

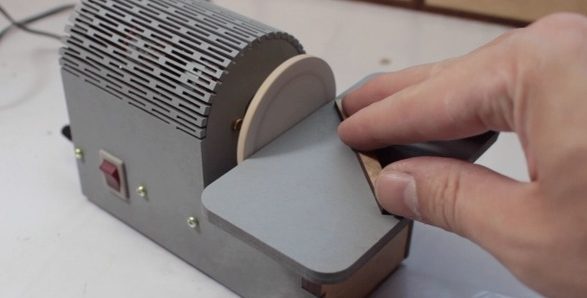

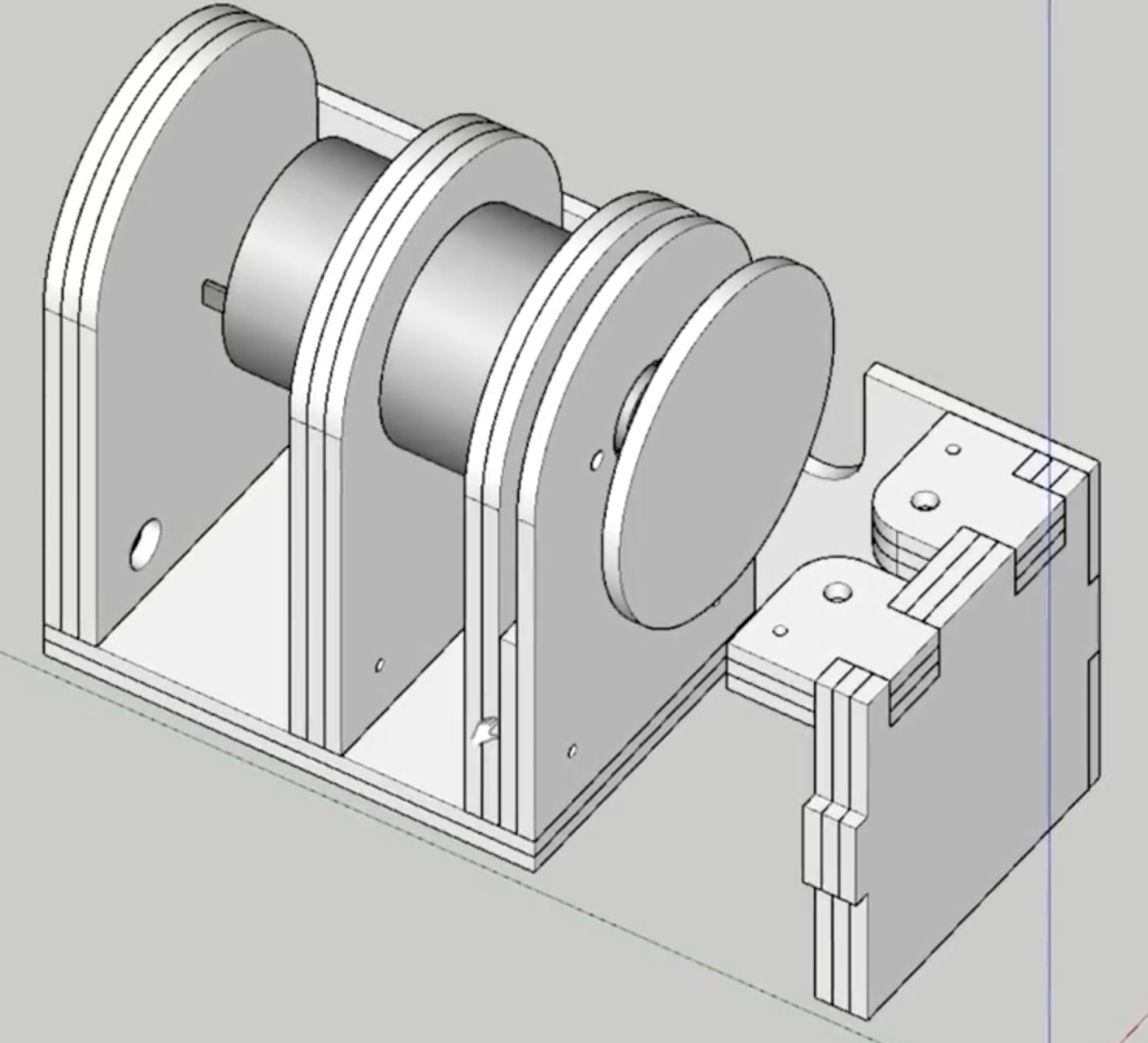

Adorable Desktop Disc Sander Warms Our Hearts And Our Parts

Casually browsing YouTube for “shop improvements” yields a veritable river of project ideas, objects for cat amusement, and 12 INCREDIBLE SHOP HACKS YOU WON’T BELIEVE, though some of these are of predictably dubious value. So you might imagine that when we found [Henrique]’s adorable disc sander we dismissed it out of hand, how useful could such a tiny tool be? But then we remembered the jumbo tub o’ motors on the shelf and reconsidered, maybe a palm sized sander has a place in the tiny shop.

Electrically the build is a simple as can be. It’s just a brushed DC motor plugged into a wall wart with a barrel jack and a toggle switch. But what else does it need? This isn’t a precision machine tool, so applying the “make it out of whatever scrap” mindset seems like a much better fit than figuring out PWM control with a MOSFET and a microcontroller.

Electrically the build is a simple as can be. It’s just a brushed DC motor plugged into a wall wart with a barrel jack and a toggle switch. But what else does it need? This isn’t a precision machine tool, so applying the “make it out of whatever scrap” mindset seems like a much better fit than figuring out PWM control with a MOSFET and a microcontroller.

There are a couple of neat tricks in the build here. The most obvious is the classic laser-cut living hinge that we love so much. [Henrique] mentions that he buys MDF in 3 mm sheets for easy storage, so each section of the frame is built from layers that he laminates with glue himself. This trades precision and adds steps, but also give him a little flexibility. It’s certainly easier to add layers of thin stock together than it would be to carve out thicker pieces. Using the laser to precisely cut holes which are then match drilled through into the rest of the frame is a nice build acceleration too. The only improvement we can imagine would be using a shaft with a small finger chuck (like a Dremel) so it could use standard rotary tool bits to avoid making sanding disks by hand.

What could a tool like this be used for? There are lots of parts with small enough features to be cleaned up by such a small tool. Perhaps those nasty burrs after cutting off a bolt? Or trimming down mousebites on the edges of PCBs? (Though make sure to use proper respiration for cutting fiberglass!)

If you want to make one of these tools for your own desk, the files are here on Thingiverse. And check out the video overview after the break.

Continue reading “Adorable Desktop Disc Sander Warms Our Hearts And Our Parts”

3D Printed Brushed Motor Is Easy To Visualize

A motor — or a generator — requires some normal magnets and some electromagnets. The usual arrangement is to have a brushed commutator that both powers the electromagnets and switches their polarity as the motor spins. Permanent magnets don’t rotate and attract or repel the electromagnets as they swing by. That can be a little hard to visualize, but if you 3D Print [Miller’s Planet’s] working model — or just watch the video below — you can see how it all works.

We imagine the hardest part of this is winding the large electromagnets. Getting the axle — a nail — centered is hard too, but from the video, it looks like it isn’t that critical. There was a problem with the link to the 3D model files, but it looks like this one works.

Continue reading “3D Printed Brushed Motor Is Easy To Visualize”