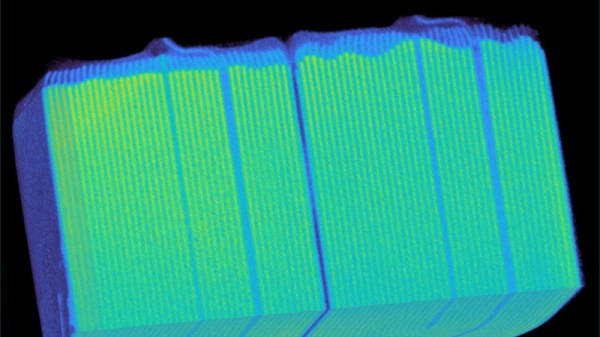

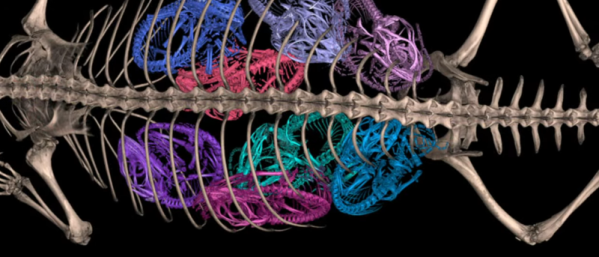

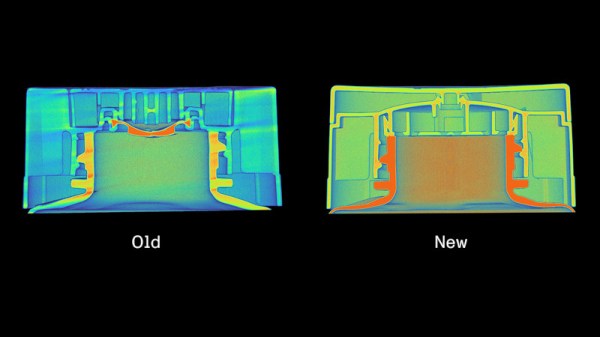

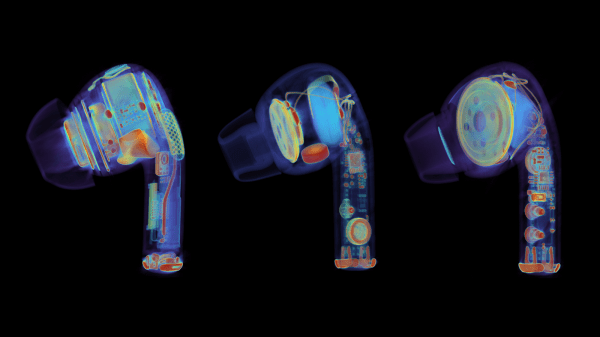

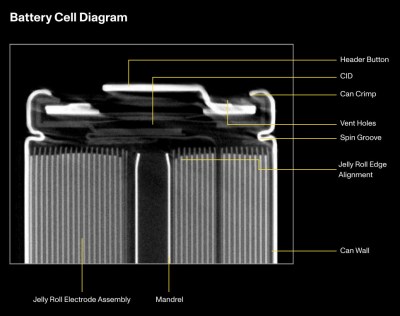

[Alex Hao] and [Andreas Bastian] of Lumafield recently visited with [Adam Savage] to document their findings after performing X-ray computed tomography scans on over 1,000 18650 lithium-ion batteries.

The short version — don’t buy cheap cells! The cheaper brands were found to have higher levels of manufacturing defects which can lead them to being unsafe. All the nitty-gritty details are available in the report, which can be downloaded for free from Lumafield, as well as the Tested video they did with [Adam] below.

The short version — don’t buy cheap cells! The cheaper brands were found to have higher levels of manufacturing defects which can lead them to being unsafe. All the nitty-gritty details are available in the report, which can be downloaded for free from Lumafield, as well as the Tested video they did with [Adam] below.

Actually we’ve been talking here at Hackaday over at our virtual water-cooler (okay, okay, our Discord server) about how to store lithium-ion batteries and we learned about this cool bit of kit: the BAT-SAFE. Maybe check that out if you’re stickler for safety like us! (Thanks Maya Posch!)

We have of course heard from [Adam Savage] before, check out [Adam Savage] Giving A Speech About The Maker Movement and [Adam Savage]’s First Order Of Retrievability Tool Boxes.