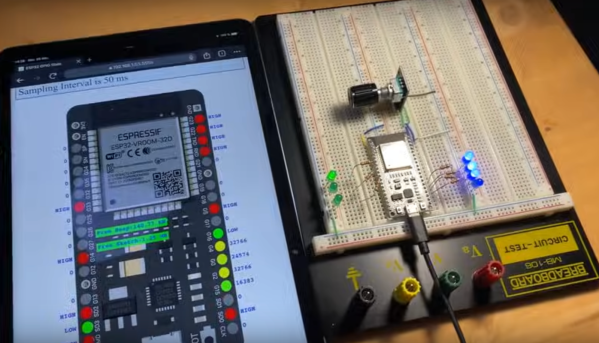

The ESP32 has been a go-to microcontroller platform for a while now, thanks to its versatile capabilities, integrated Wi-Fi and Bluetooth connectivity, and low power consumption. It’s ideal for a wide range of projects especially those revolving around IoT, partially because of all of the libraries and tools available for it now. The latest tool from [The Last Outpost Workshop] adds a feature we didn’t know we wanted until now: a webserver showing real-time updates of what all of the GPIO pins are doing.

The live GPIO pin monitoring library sets up the ESP32 to stream information about what all of the pins are doing in real time to a webserver, which displays the information as a helpful graphic. The demonstration in the video below shows and example troubleshooting a situation where the code is correct but there’s a mistake in the wiring, helping to quickly identify the problem and hopefully eliminating a wild goose chase for a bug in the software. The library can be quickly installed using the Arduino IDE and only requires the use of one other library and a few lines of code to get everything up and running.

As far as a debugging tool goes, something like this could save a lot of us a significant amount of time, especially with how easy it is to set up. A real-time look into the pins and their behavior, including those set up for PWM, is invaluable for plenty of situations. Of course if you’re building something like a real-time operating system that needs responses within a very specific interval you may want to look at more in-depth strategies for probing the GPIO.

Thanks to [Bob] for the tip!

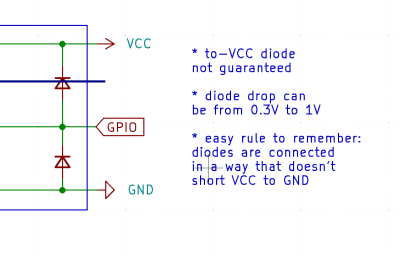

Thankfully, in modern-day Western climates and with modern tech, you are not likely to encounter ESD-caused problems, but they were way more prominent back in the day. For instance, older hackers will have stories of how FETs were more sensitive, and touching the gate pin mindlessly could kill the FET you’re working with. Now, we’ve fixed this problem, in large part because we have added ESD-protective diodes inside the active components most affected.

Thankfully, in modern-day Western climates and with modern tech, you are not likely to encounter ESD-caused problems, but they were way more prominent back in the day. For instance, older hackers will have stories of how FETs were more sensitive, and touching the gate pin mindlessly could kill the FET you’re working with. Now, we’ve fixed this problem, in large part because we have added ESD-protective diodes inside the active components most affected.