What’s the best way to learn electronics? It’s a pithy question to ask a Hackaday audience, most of whom are at least conversant in the field already. Those who already have learned often have just their own perspective to draw upon—how they themselves learned. Some of you may have taught others. I want to explore what works and what doesn’t.

Hobbyists Learn Differently Than Students

One thing I can say straight off is that students learn differently than people who learn at home. Hobbyists have the advantage of actually being interested, which is a quality a student may not enjoy. People have been teaching themselves electronics since the beginning, with analog projects–Heathkit models, BEAM robots, and ham radio sets–evolving into purely digital projects.

One thing I can say straight off is that students learn differently than people who learn at home. Hobbyists have the advantage of actually being interested, which is a quality a student may not enjoy. People have been teaching themselves electronics since the beginning, with analog projects–Heathkit models, BEAM robots, and ham radio sets–evolving into purely digital projects.

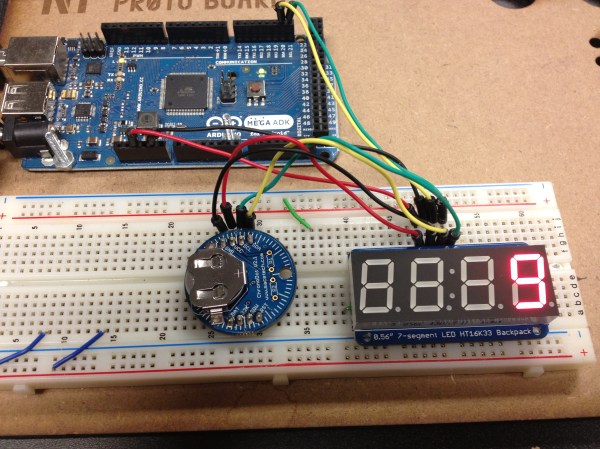

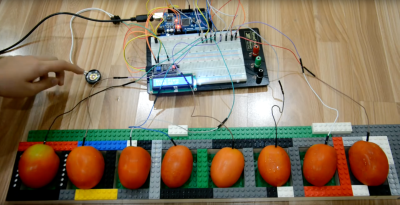

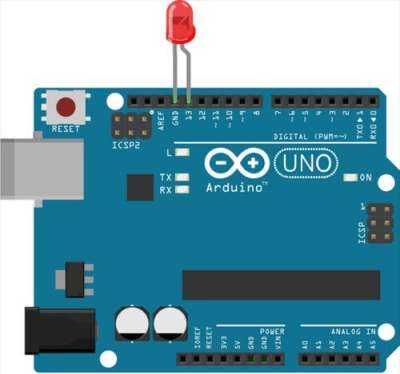

Let’s face it, Arduinos lower the bar like nothing else. There’s a reason why the Blink sketch has become the equivalent to “Hello World”. Dirt cheap and easily configured microcontrollers combined with breakout boards make it easy for anyone to participate.

However, ask any true EE and that person will tell you that following wiring diagrams and plugging in sensor boards from Sparkfun only teaches so much. You don’t bone up on terms like hysteresis or bias by building something from uCs and breakout boards. But do you need to? If you are truly interested in electronics and learn by making those Adafruit or Sparkfun projects, sooner or later you’ll want to make your own breakout boards. You’ll learn how to design your own circuit boards and figure out why things work and why they don’t. I don’t need to tell you the Internet has all the answers a neophyte needs–but the interest has to be there in the first place.

What’s the Best Way to Learn in the Classroom?

There is a product category within robotics kits that consists of “educational rovers” designed to be purchased in group lots by teachers so that each student or small group gets one. These rovers are either pre-built or mostly built—sure, you get to screw in motor mounts, but all the circuit boards are already soldered up for you, surface mount, no less. They come pre-configured for a variety of simple tasks like line following and obstacle avoidance. The Makeblock mBot is an example.

There is a product category within robotics kits that consists of “educational rovers” designed to be purchased in group lots by teachers so that each student or small group gets one. These rovers are either pre-built or mostly built—sure, you get to screw in motor mounts, but all the circuit boards are already soldered up for you, surface mount, no less. They come pre-configured for a variety of simple tasks like line following and obstacle avoidance. The Makeblock mBot is an example.

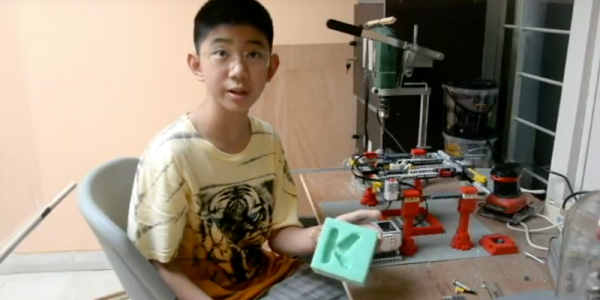

I think it’s part of that whole “learn coding” initiative, where the idea is to minimize the assembly in order to maximize the coding time. Insofar as soldering together a kit of through-hole components teaches about electronics, these bots mostly don’t do it. By all appearances, if there is a best way to learn electronics, this an’t it. However, regardless of what kind of project the teacher puts in front of the student, it still has to generate some sort of passion. What those robots provide is a moment of coolness that ignites the firestorm of interest.

I once led a soldering class that used Blinky Grids by Wayne and Layne as the focus. This is a fantastic kit that guides you through building a small LED matrix. It’s particularly cool because it can be programmed over a computer monitor with light sensors interacting with white and black squares on the company’s web site. When my students finished their grids, they all worked and had unique messages scrolling through. Now, that is a payoff. I’m not saying that any of those folks became hardware hackers as a result of my class, but it beat the hell out of a Christmas tree, am I right?

Getting back to that rover, what must be acknowledged is that the rover itself is the payoff, and that’s only as far as it goes if everyone loses interest. However, a lot of those rovers have expansion possibilities like bolting on another sensor or changing the method of programming–for instance, the mBot has both a graphic programming interface and can also be reflashed with a regular old Arduino bootloader.

Readers, share in comments your own perspective. How did you learn? How would you teach others?