Hacker dads often have great plans for all the fun projects they’ll build for their kids. Reality often intrudes, though, creating opportunities for hacker grandfathers who might have more time and resources to tackle the truly epic kid hacks. Take, for instance, [rwreagan] and the quarter-scale model railroad he built for his granddaughter.

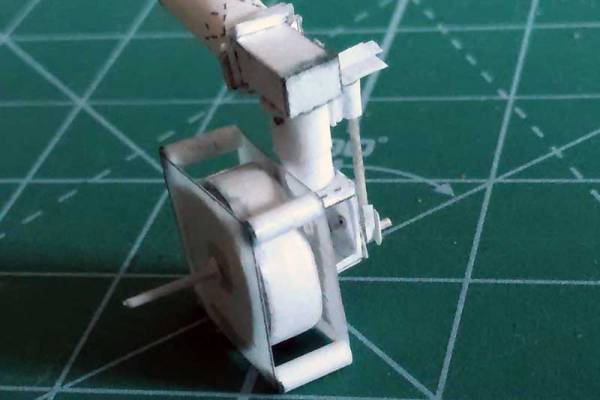

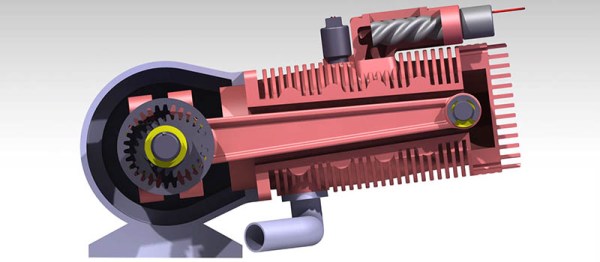

Taking inspiration from a 1965 issue of Popular Mechanics, grandpa hit this one out of the park. Attention to detail and craftsmanship are evident from the cowcatcher to the rear coupler of this 4-2-0 steam engine replica, and everywhere along the 275 feet of wooden track — that’s almost a quarter-mile at scale. The locomotive runs on composite wood and metal flanged wheels powered by pair of 350-watt motors and some 12-volt batteries; alas, no steam. The loco winds around [rwreagan]’s yard through a right-of-way cut into the woods and into a custom-built engine house that’ll make a great playhouse. And there are even Arduino-controlled crossbucks at the grade crossing he uses for his tractor on lawn mowing days.

The only question here is: will his granddaughter have as much fun using it as he had building it? We’ll guess yes because it looks like a blast all around. Other awesome dad builds we’ve covered include this backyard roller coaster and a rocketship treehouse.

Continue reading “And The Grandfather Of The Year Award Goes To…”

Last week we saw

Last week we saw