You’ve probably heard of the infamous rule 34, but we’d like to propose a new rule — call it rule 35: Anything that can be used for nefarious purposes will be, even if you can’t think of how at the moment. Case in point: apparently there has been an uptick in people using AirTags to do bad things. People have used them to stalk people or to tag cars so they can be found later and stolen. According to [Fabian Bräunlein], Apple’s responses to this don’t consider cases where clones or modified AirTags are in play. To prove the point, he built a clone that bypasses the current protection features and used it to track a willing experimental subject for 5 days with no notifications.

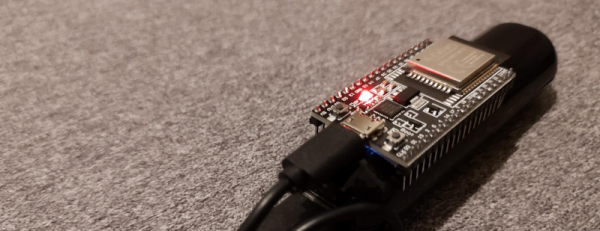

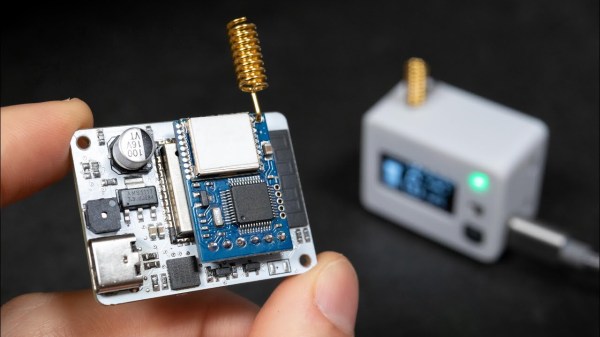

According to the post, Apple says that AirTags have serial numbers and beep when they have not been around their host Apple device for a certain period. [Fabian] points out that clone tags don’t have serial numbers and may also not have speakers. There is apparently a thriving market, too, for genuine tags that have been modified to remove their speakers. [Fabian’s] clone uses an ESP32 with no speaker and no serial number.

The other protection, according to Apple, is that if they note an AirTag moving with you over some period of time without the owner, you get a notification. In other words, if your iPhone sees your own tag repeatedly, that’s fine. It also doesn’t mind seeing someone else’s tags if they are near you. But if your phone sees a tag many times and the owner isn’t around, you get a notification. That way, you can help identify random tags, but you’ll know if someone is trying to track you. [Fabian] gets around that by cycling between 2,000 pre-loaded public keys so that the tracked person’s device doesn’t realize that it is seeing the same tag over and over. Even Apple’s Android app that scans for trackers is vulnerable to this strategy.

Even for folks who aren’t particularly privacy minded, it’s pretty clear a worldwide network of mass-market devices that allow almost anyone to be tracked is a problem. But what’s the solution? Even the better strategies employed by AirGuard won’t catch everything, as [Fabian] explains.

This isn’t the first time we’ve had a look at privacy concerns around AirTags. Of course, it is always possible to build a tracker. But it is hard to get the worldwide network of Bluetooth listeners that Apple has.