In case you haven’t heard, we have a 3D printing contest going on right now. It’s the Repairs You Can Print Contest. The idea is simple: show off how you repaired something with a 3D printer. Prizes include $100 in Tindie credit, and as a special prize for students and organizations (think hackerspaces), we’re giving away a few Prusa i3 MK3 printers.

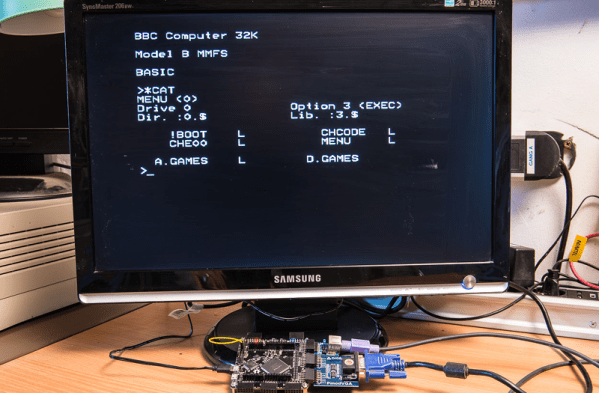

[Drygol] has made a name for himself repairing various ‘home’ computers over the years, and this time he’s back showing off the mods and refurbishments he’s made to a pile of Amiga 500s. This time, he’s installing some new RAM chips, fixing some Guru Meditations by fiddling with the pins on a PLCC, adding a built-in modulator, installing a dual Kickstart ROM, and installing a Gotek floppy adapter. It’s awesome work that puts all the modern conveniences into this classic computer.

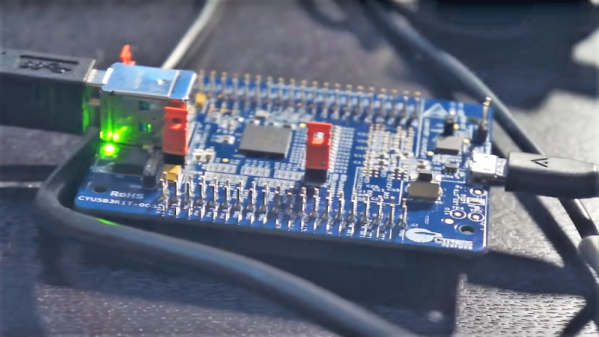

Here’s an FPGA IoT Controller. It’s a Cyclone IV and a WiFi module stuffed into something resembling an Arduino Mega. Here’s the question: what is this for? There are two reasons you would use an FPGA, either doing something really fast, or doing something so weird normal microcontrollers just won’t cut it. I don’t know if there is any application of IoT that overlaps with FPGAs. Can you think of something? I can’t.

Tide pods are flammable.

You know what’s cool? Sparklecon. It’s a party filled with a hundred pounds of LEGO, a computer recycling company, a plasmatorium, and a hackerspace, tucked away in an industrial park in Fullerton, California. It’s completely chill, and a party for our type of people — those who like bonfires, hammer Jenga, beer, and disassembling fluorescent lamps for high voltage transformers.

A few shoutouts for Sparklecon. The 23b Hackerspace is, I guess, the main host here, or at least the anchor. Across the alley is NUCC, the National Upcycled Computing Collective. They’re a nonprofit that takes old servers and such, refurbishes them, and connects them to projects like Folding@Home and SETI@Home. This actually performs a service for scientists, because every moron is mining Bitcoin and Etherium now, vastly reducing the computational capabilities of these distributed computing projects. Thanks, OSH Park, for buying every kind of specialty pizza at Pizza Hut. I would highly encourage everyone to go to Sparklecon next year. This is the fifth year, and it’s getting bigger and better every time.