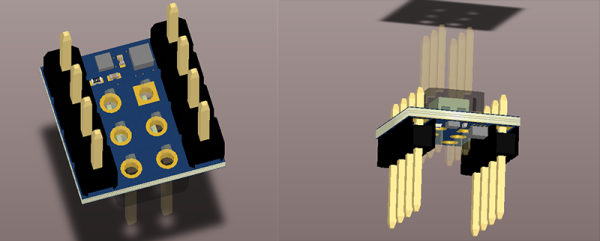

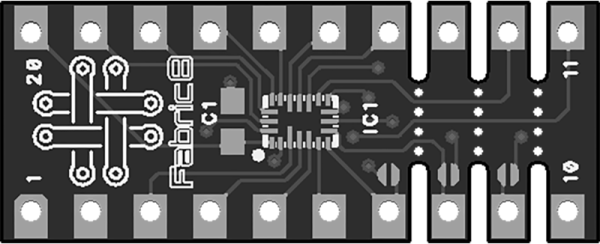

There are a few development boards entered in this year’s Hackaday Prize, and most of them cover well-tread ground with their own unique spin. There are not many FPGA dev boards entered. Whether this is because programmable logic is somehow still a dark art for solder jockeys or because the commercial offerings are ‘good enough’ is a matter of contention. [antti lukats] is doing something that no FPGA manufacturer would do, and he’s very good at it. Meet DIPSY, the FPGA that fits in the same space as an 8-pin DIP.

FPGAs are usually stuffed into huge packages – an FPGA with 100 or more pins is very common. [antti] found the world’s smallest FPGA. It’s just 1.4 x 1.4mm on a wafer-scale 16-pin BGA package. The biggest problem [antti] is going to have with this project is finding a board and assembly house that will be able to help him.

The iCE40 UltraLite isn’t a complex FPGA; there are just 1280 logic cells and 7kByte of RAM in this tiny square of programmable logic. That’s still enough for a lot of interesting stuff, and putting this into a convenient package is very interesting. The BOM for this project comes out under $5, making it ideal for experiments in programmable logic and education.

A $5 FPGA is great news, and this board might even work with the recent open source toolchain for iCE40 FPGAs. That would be amazing for anyone wanting to dip their toes into the world of programmable logic.