How often have you stood in the supermarket wondering about the inventory level in the fridge at home? [Mike] asked himself this question one time too often and so he decided to install a webcam in his fridge along with a Raspberry Pi and a light sensor to take a picture every time the fridge is opened — uploading it to a webserver for easy remote access.

internet of things156 Articles

OpenThread, A Solution To The WiFi Of Things

The term ‘Internet of Things’ was coined in 1999, long before every laptop had WiFi and every Starbucks provided Internet for the latte-sucking masses. Over time, the Internet of Things meant all these devices would connect over WiFi. Why, no one has any idea. WiFi is terrible for a network of Things – it requires too much power, the range isn’t great, it’s beyond overkill, and there’s already too many machines and routers on WiFi networks, anyway.

There have been a number of solutions to this problem of a WiFi of Things over the years, but none have caught on. Now, finally, there may be a solution. Nest, in cooperation with ARM, Atmel, dialog, Qualcomm, and TI have released OpenThread, an Open Source implementation of the Thread networking protocol.

The physical layer for OpenThread is 802.15.4, the same layer ZigBee is based on. Unlike ZigBee, the fourth, fifth, and sixth layers of OpenThread look much more like the rest of the Internet. OpenThread features IPv6 and 6LoWPAN, true mesh networking, and requires only a software update to existing 802.15.4 radios.

OpenThread is OS and platform agnostic, and interfacing different radios should be relatively easy with an abstraction layer. Radios and networking were always the problem with the Internet of Things, and with OpenThread – and especially the companies supporting it – these problems might not be much longer.

Connect All Your IoT Through Your Pi 3

If you’re playing Hackaday Buzzword Bingo, today is your lucky day! Because not only does this article contain “Pi 3” and “IoT”, but we’re just about to type “ESP8266” and “home automation”. Check to see if you haven’t filled a row or something…

Seriously, though. If you’re running a home device network, and like us you’re running it totally insecurely, you might want to firewall that stuff off from the greater Interwebs at least, and probably any computers that you care about as well. The simplest way to do so is to keep your devices on their own WiFi network. That shiny Pi 3 you just bought has WiFi, and doesn’t use so much power that you’d mind leaving it on all the time.

Even if you’re not a Linux networking guru, [Phil Martin]’s tutorial on setting up the Raspberry Pi 3 as a WiFi access point should make it easy for you to use your Pi 3 as the hub of your IoT system’s WiFi. He even shows you how to configure it to forward your IoT network’s packets out to the real world over wired Ethernet, but if you can also use the Pi 3 as your central server, this may not even be necessary. Most of the IoT services that you’d want are available for the Pi.

Those who do want to open up to the world, you can easily set up a very strict firewall on the Pi that won’t interfere with your home’s normal WiFi. Here’s a quick guide to setting up iptables on the Pi, but using even friendlier software like Shorewall should also get the job done.

Still haven’t filled up your bingo card yet? “Arduino!”

ESP8266 Based Irrigation Controller

If you just want to prevent your garden from slowly turning into a desert, have a look at the available off-the-shelf home automation solutions, pick one, lean back and let moisture monitoring and automated irrigation take over. If you want to get into electronics, learn PCB design and experience the personal victory that comes with all that, do what [Patrick] did, and build your own ESP8266 based irrigation controller. It’s also a lot of fun!

[Patrick] already had a strong software background and maintains his own open source home automation system, so building his own physical hardware to extend its functionality was a logical step. In particular, [Patrick] wanted to add four wirelessly controlled valves to the system.

Red Bricks: Alphabet To Turn Off Revolv’s Lights

Revolv, the bright red smart home hub famous for its abundance of radio modules, has finally been declared dead by its founders. After a series of acquisitions, Google’s parent company Alphabet has gained control over Revolv’s cloud service – and they are shutting it down.

Customers who bought into Revolv’s vision of a truly connected and automated smart home hub featuring 7 different physical radio modules to connect all their devices will soon become owners of significantly less useful, red bricks due to the complete shutdown of the service on May 15, 2016.

Continue reading “Red Bricks: Alphabet To Turn Off Revolv’s Lights”

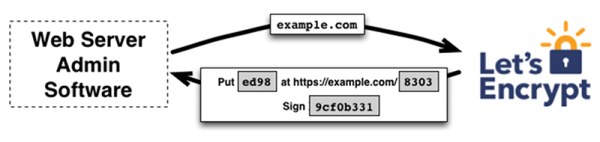

Anti-Hack: Free Automated SSL Certificates

You want to put your credit card number into a web site. You know to look for a secure web site. But what does that really prove? And now that so many electronic projects have Web servers (ok, I’ll say it… the Internet of Things), do you need to secure your web server?

There was a time when getting a secure certificate (at least one that was meaningful) cost a pretty penny. However, a new initiative backed by some major players (like Cisco, Google, Mozilla, and many others) wants to give you a free SSL certificate. One reason they can afford to do this is they have automated the verification process so the cost to provide a certificate is very low.

Continue reading “Anti-Hack: Free Automated SSL Certificates”

One Man’s Quest To Spend Less TIme In The Basement

[Lars] has a second floor apartment, and the washing machines and clothes dryers are in the basement. This means [Lars] has spent too much time walking down to the basement to collect his laundry, only to find out there is 15 minutes left in on the cycle. There are a few solutions to this: leave your load in the washer like an inconsiderate animal, buy a new, fancy washer and dryer with proprietary Internet of Things™ software, or hack together a washer and dryer monitoring solution. We all know what option [Lars] chose.

Connecting a Pi to the Internet and serving up a few bits of data is a solved problem. The hard part is deciding which bits to serve. Washers and dryers all have a few things in common: they both use power, they both move and shake, they make noise, and their interfaces change during the wash cycle. [Lars] wanted a device that could be used with washers and dryers, and could be used with other machines in the future. He first experimented with a microphone, capturing the low rumble of a washer sloshing about and a dryer tumbling a load of laundry. It turns out an accelerometer works just as well, and with a sensor securely fastened to a washer or dryer, [Lars] can get a pretty good idea if it’s running or not.

With a reliable way to tell if a washer or dryer is still running, [Lars] only had to put this information on his smartphone. He ended up using PushBullet, and quickly had an app on his phone that told him if his laundry was done.

The Raspberry Pi Zero contest is presented by Hackaday and Adafruit. Prizes include Raspberry Pi Zeros from Adafruit and gift cards to The Hackaday Store!

See All the Entries || Enter Your Project Now!