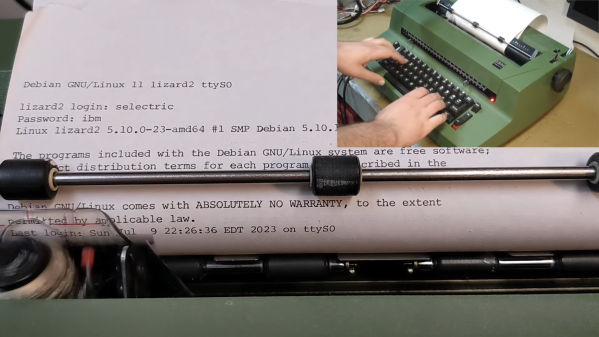

If there’s only lesson to be learned from [alnwlsn]’s conversion of an IBM Selectric typewriter into a serial terminal for Linux, it’s that we’ve been hanging around the wrong garbage cans. Because that’s where he found the donor machine for this project, and it wasn’t even the first one he’s come across in the trash. The best we’ve ever done is a nasty old microwave.

For being a dumpster find, the Selectric II was actually in pretty decent shape. The first couple of minutes of the video after the break show not only the minimal repairs needed to get the typewriter back on its feet, but also a whirlwind tour of the remarkably complex mechanisms that turn keypresses into characters on the page. As it turns out, knowing how the mechanical linkages work is the secret behind converting the Selectric into a teletype, entirely within the original enclosure and with as few modifications to the existing mechanism as possible.

Keypresses are mimicked with a mere thirteen solenoids — six for the “latch interposers” that interface with the famous whiffletree mechanism that converts binary input to a specific character on the typeball, and six more that control thinks like the cycle bail and control keys. The thirteenth solenoid controls an added bell, because every good teletype needs a bell. For sensing the keypresses — this is to be a duplex terminal, after all — [alnwlsn] pulled a page from the Soviet Cold War fieldcraft manual and used opto-interrupters to monitor the positions of the latch interposers as keys are pressed, plus more for the control keys.

The electronics are pretty straightforward — a bunch of MOSFETs to drive the solenoids, plus an AVR microcontroller. The terminal speaks RS-232, as one would expect, and within the limitations of keyboard and character set differences over the 50-odd years since the Selectric was introduced, it works fantastic as a Linux terminal. The back half of the video is loaded with demos, some of which aptly demonstrate why a lot of Unix commands look the way they do, but also some neat hybrid stuff, like a ChatGPT client.

Hats off to [alnwlsn] for tackling a difficult project while maintaining the integrity of the original hardware.

Continue reading “Selectric Typewriter Goes From Trash Can To Linux Terminal”